The pandemic is wreaking havoc in loan-laden white-collar workers’ households; ‘I will never claw my way out of this situation’

Until mid-March, Alysse Hopkins earned a comfortable living in Rockland County, N.Y., representing clients in foreclosure cases and personal injury lawsuits.

In a good year, the 43-year-old lawyer and her husband, Ian Boschen, 41, together brought in about $175,000, the couple said—enough to cover the mortgage, two car leases, student loans, credit cards, and assorted costs of raising two daughters in the New York City suburbs.

New Covid-19 Layoffs Make Job Reductions Permanent

After the coronavirus halted many foreclosures and closed courts, her work dried up. Unemployment benefits have helped, Ms. Hopkins said, but the family is running low on savings and can’t keep up with $9,000 in monthly debt payments including mortgage installments. “It frustrates me to not be able to earn a living,” she said. “I have a law degree, almost 20 years of practice.”

Millions of Americans have lost jobs during a pandemic that kept restaurants, shops, and public institutions closed for months and hit the travel industry hard. While lower-wage workers have borne much of the brunt, the crisis is wreaking a particular kind of havoc on the debt-laden middle class.

Debt didn’t present a major problem before the coronavirus. The job market was booming and median household incomes were rising, allowing families to keep up with payments.

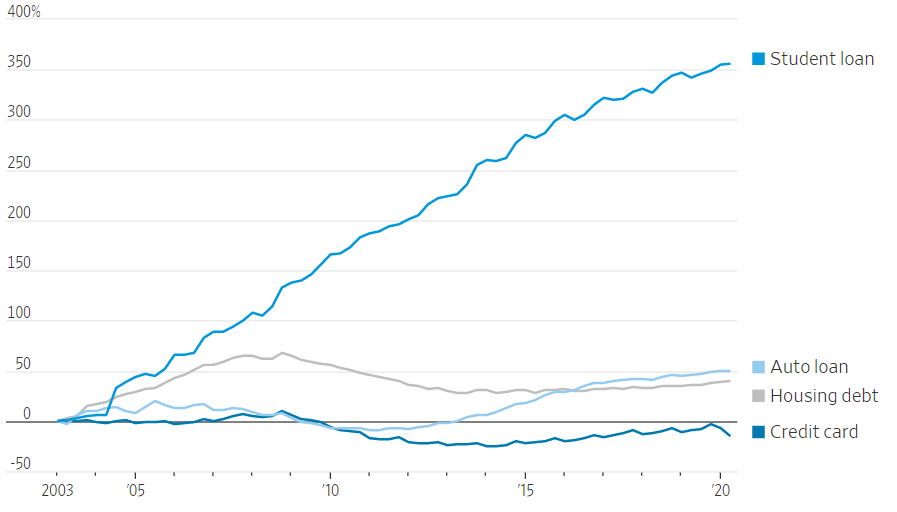

American families with nonhousing debt making over $98,018 a year in pre-tax income owed an average of nearly $92,000 of such debt in 2016. That’s up 32% from 2004, adjusted for inflation, according to an analysis of Federal Reserve data by the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit research group.

Average nonhousing debt owed by families making $52,655 to $98,018 rose about 33% over the 12 years to $33,378.

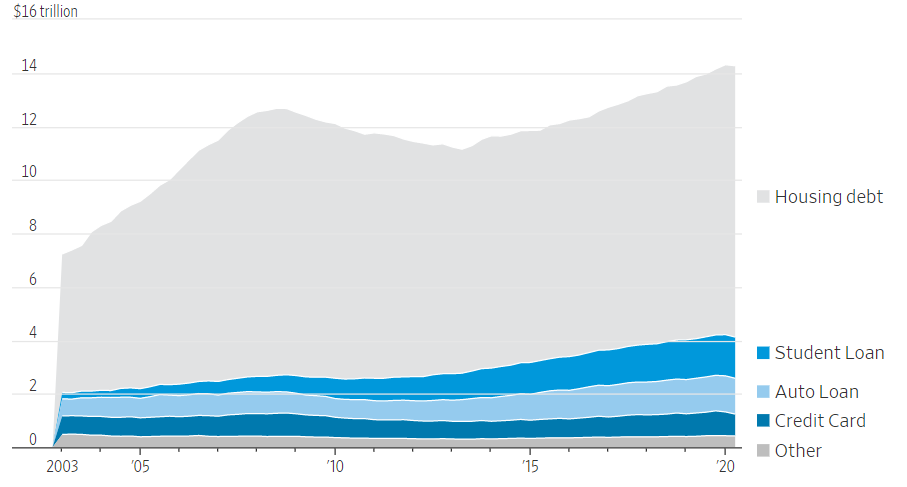

Before the pandemic, Americans had amassed $4.2 trillion in consumer debt, excluding mortgages, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, a record even when adjusting for inflation. Housing debt added an additional $10 trillion to the tally.

The coronavirus has spared few industries and expanded unemployment benefits designed to replace the average American income didn’t cover all the lost pay of higher-earning workers, especially in or near expensive cities. The extra $600 weekly payments expired in July, putting them even further behind.

“What I see happening here is a core assault on successful college-educated families, which are the new breed of middle-class American families,” said Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “There’s a professional workforce that’s getting slammed.”

Roughly six months into the pandemic, many lenders that let borrowers skip monthly payments now expect to get paid again. They have set aside billions of dollars to cover potential losses on soured consumer loans—an acknowledgment that America’s decadelong debt binge has come to an end.

Credit-card debt has fallen in recent months. But with a big chunk of government assistance gone, Congress is still haggling over the second round of coronavirus relief. President Trump signed an executive order in August to provide an extra $300 a week in federal unemployment benefits. The payments haven’t been distributed by every state yet, and Democrats say the president’s order violated congressional-spending authority.

White-collar pain

Unemployment has fallen from its pandemic peak of near 15%, but the rate stood at 8.4% in August, up from 3.5% in February, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unemployment for the arts, design, media, sports, and entertainment was 12.7% in August, more than triple its year-earlier level. In education, it more than doubled to 10.2%. Sales and office unemployment was 7.8% in August, up from 3.8% in August 2019.

Architects and engineers, who earn $1,826 in average weekly pretax income, well above the $1,389 average among full-time wage and salaried workers, have seen unemployment rise to 3.7% from 0.8% a year earlier. Unemployment for computer and math occupations, which earn $1,919 a week on average, more than tripled to 4.6%.

It could get worse. “The pain so far in the economy has largely been at the lower end of the pay scale,” said Discover Financial Services Chief Executive Roger Hochschild, adding that many of “the white-collar layoffs are still to come.”

Lynn Scott-White, 47, was furloughed from her job as a corporate travel agent at the end of March. Before the pandemic, she and her husband together earned roughly $150,000, she said.

The Denton, Texas, couple pay $4,400 a month on their mortgage, four-car loans and leases, and student debt, Ms. Scott-White said. The Minimum required monthly credit-card payments total about $700. The debt was manageable pre-pandemic, she said.

She deferred lease payments on her Infiniti QX60 for three months and started playing again with unemployment benefits. Her husband traded in his Ford F-150 in August for a lower-cost car and reduced his original monthly payment of $820 by about $100, and his income covers the $2,100 mortgage.

PHOTO: JUSTIN CLEMONS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

After about 24 years in the travel industry, Ms. Scott-White is preparing to switch careers, concluding it could be a long time before corporate travel returns to previous levels. In August, her employer gave her three options: severance of a week’s pay for each year employed, unpaid leave until late March, or continue on furlough.

She resigned, opting to take the severance. She returned to college last month to complete a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology to pursue a sports medicine career. She borrowed $5,000 against her 401(k) to help pay for it. “I didn’t think I would have to do this,” she said. “I’m trying to decide what I want to be when I grow up.”

By some measures, the outlook for higher-earning workers appears worse than during the 2008 financial crisis. In August, about 3.3 million people age 25 and over with bachelor’s degrees or higher were unemployed, up from 1.2 million in February, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. During the last downturn, that number peaked at about 2.2 million.

Postings for jobs with salaries over $100,000 were down 19% in August from April, while postings for all other salary categories increased, according to job-search site ZipRecruiter Inc.

American Airlines Group Inc. and United Airlines Holdings Inc. have outlined plans to furlough or lay off thousands of employees on Oct. 1, when federal aid expires unless they receive more government assistance. Business-software company Salesforce.com Inc. is eliminating 1,000 jobs; a spokeswoman said the company is also adding 4,000 jobs over the next six months.

14 work-from-home jobs that pay up to six figures—and how to get them

MGM Resorts International and Stanley Black & Decker Inc. notified some furloughed employees they would be laid off. The companies said they have brought back, or expect to bring back, many of these employees.

America’s biggest banks have indicated they are preparing for a protracted downturn to hurt businesses in industries that weren’t immediately affected by shutdowns.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. says it expects the U.S. to add roughly 5.4 million jobs in the third and fourth quarters. That would leave the U.S. economy with about 9.2 million fewer jobs since February.

“The pandemic has a grip on the economy,” Citigroup Inc. CEO Michael Corbat said when the bank reported second-quarter earnings in July, “and it doesn’t seem likely to loosen until vaccines are widely available. This month, the bank said many customers that previously enrolled in deferment programs are making payments.

‘Very dire’

Terri Smith, 64, said her job analyzing legal expenses for her employer was eliminated in a round of cost-cutting. Even with the extra $600 a week, unemployment didn’t cover her lost earnings, and she is now down to $285 after tax in weekly unemployment benefits.

The monthly mortgage payment on her Charlotte, N.C., home is $1,550, she said. Her car payment is $550. Health insurance costs $600 a month, and a recent hospital visit cost $7,500 in out-of-pocket expenses. She has dipped into savings to keep up with bills and is thinking about withdrawing from her 401(k) or signing up for loan-deferment programs until she can find a job.

“I don’t have a plan. It’s very dire,” she said. “I’m getting very nervous.”

Many people who have jobs are struggling with pay cuts. As of August, 17 million workers were getting paid less due to the pandemic, said Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. Some 9.5 million took pay cuts; the remaining 7.5 million are working fewer hours, he said.

Steven Sickinger’s income fell sharply in the spring, he said, when customers stopped coming to the auto repair shop he managed. Concerned that the shop was at risk of shutting down, Mr. Sickinger, 55, quit and took another job he considered more secure making $50,000—35% less than the $77,000 he made in 2019.

The pay cuts have made it difficult for the Tucson, Ariz., resident to keep up with bills. He said he owes at least $24,000 on his credit cards. His credit union let him skip his roughly $655 monthly payments on the loan for his Ford F-150 in June and July. He said he hasn’t used his credit cards in months, but interest charges and late fees are pushing his balances higher. Eight of his credit cards have been reported late, he said. Pre-pandemic, his credit report showed an on-time record going back to 2014.

Before the coronavirus, his plan was to pay off the debt in about 2½ years and would then begin preparing for retirement. Now, Mr. Sickinger said, he is in the process of filing for bankruptcy: “I will never claw my way out of this situation.”

The economy is reviving in parts of the country including New York, where Ms. Hopkins lives. Most courts in the state have reopened. But law firms in New York City and Long Island that used to hire her to avoid the hour-or-more drive are now handling their cases online.

PHOTO: NATALIE KEYSSAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Ms. Hopkins is working again, taking virtual depositions, but the volume is nothing like it was. She had six assignments in August and a few so far this month. Pre-pandemic, she appeared in court on average for four to six cases a day. “I don’t know if it’s ever going to go back to that,” she said.

She and Mr. Boschen paused their $750 in-car payments for April and May. They got a one-month break on a $680 payment on a personal loan taken for a bathroom renovation. Mr. Boschen said his nearly $800 in monthly student-loan payments are deferred through December. That, and money set aside for their daughters’ summer camp, freed up enough to help cover their $3,000 monthly mortgage payment and $1,500 monthly health-insurance premium.

Ms. Hopkins’s weekly state unemployment of $441 after taxes ended last week, she said, at the same time that she received a $262 deposit, the first of her unemployment benefits tied to President Trump’s August executive order.

Ms. Hopkins said she recently took out a $36,500 Small Business Administration loan, because she qualifies as a small business through her legal work, to cover the work bills. She said she has 30 years to repay it.

WSJ / Balkantimes.press

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.