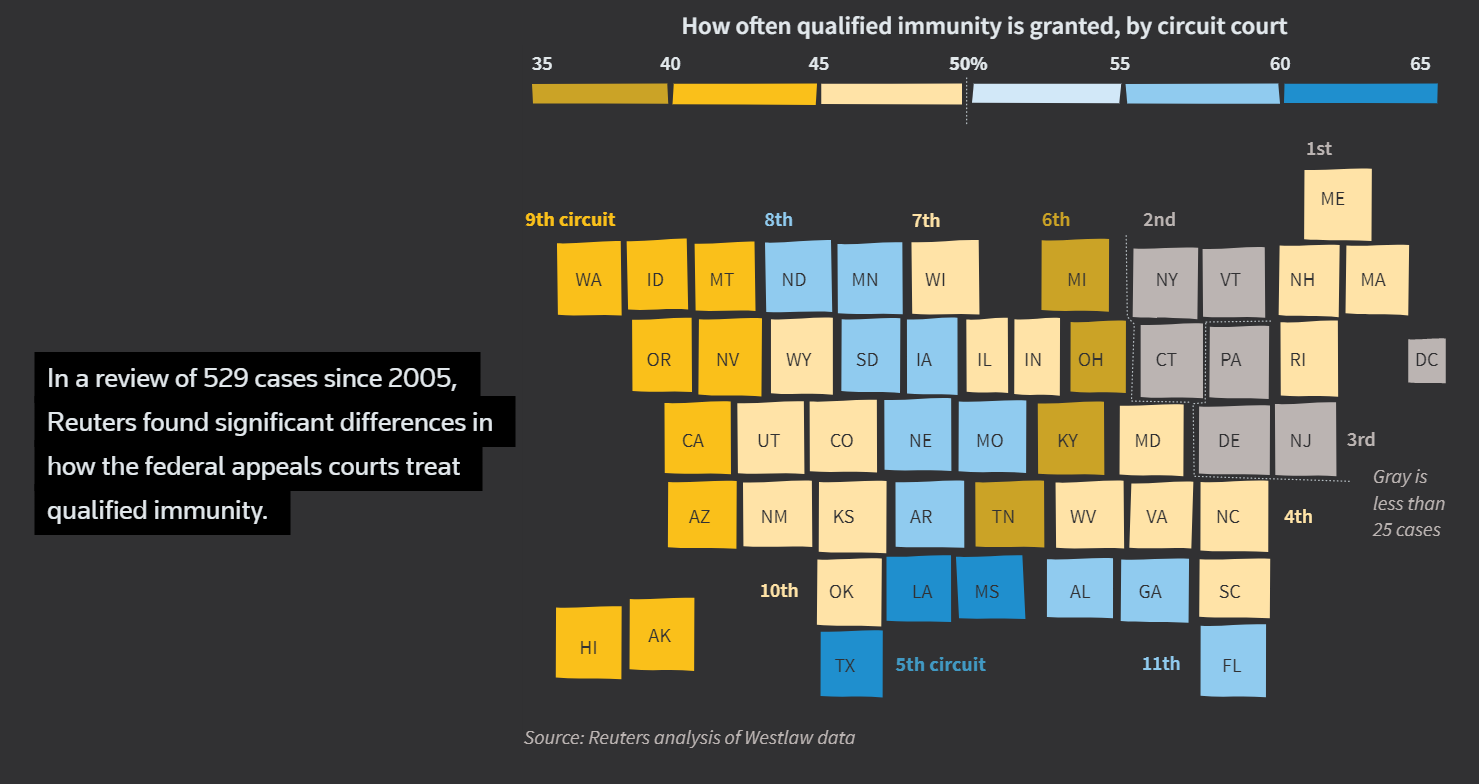

U.S. courts show wide regional disparities in granting qualified immunity, the controversial legal doctrine now under fire for protecting officers accused of excessive force.

When David Collie slipped off his shirt as he set out one sultry night to visit some friends, he didn’t know he was putting himself in grave danger. But he was.

He now fits the description: shirtless, Black, male.

Moments later, Collie lay face down on the pavement, gunned down as a possible suspect in a crime he didn’t commit.

The shooter was Fort Worth, Texas, police officer Hugo Barron. He and his partner had been looking for two shirtless Black men wanted for an armed robbery involving tennis shoes. When the cops spotted David Collie, they pulled into the apartment complex, got out of the squad car and started shouting commands at him.

Police dashboard camera video shows that Collie was walking away from the two cops as he pulled his hand out of his pocket and raised his arm. That’s when Barron fired his gun. A hollow-point bullet slammed into Collie’s back, punctured a lung and severed his spine, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down.

In the four years since then, Collie, now 37 years old, has lived in nursing homes, afflicted with infections, pressure sores, and bouts of crushing depression. As he talked about the July 2016 shooting and what it took from him, wails from an elderly patient echoed down the corridor. The odors of urine and excrement wafted in from the hall. Collie closed his eyes and exhaled. “Paralyzed over some tennis shoes? Come on, man,” he said. “You’re playing with human life here.”

Seattle Black Lives Matter clashes spark 45 arrests, 21 police injured

To many Americans, the outlines of Collie’s encounter with police have become dismayingly familiar in recent years — and all the more so since the May 25 death of George Floyd, a Black man, under the knee of a Minneapolis cop sparked mass protests against racism and aggressive police tactics. The fate of Collie’s attempt at redress has become familiar, too, and now underpins demands that police be held accountable when they kill or seriously injure people.

In a lawsuit filed in federal court in Fort Worth, Collie accused Barron of excessive force, a civil rights violation under the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. He thought that any money from a settlement or jury award would give him some measure of independence after the shooting cost him his job and derailed his plans to return to college. He also thought Barron should be held responsible for what he did.

Collie didn’t get very far. Barron, who hadn’t been disciplined or charged with any wrongdoing for the shooting, argued that he had acted reasonably on a fear that Collie was about to shoot his partner. Collie said he took his hand from his pocket to point to where he was going when Barron shot him. The judge sided with Barron — though Collie had nothing to do with the robbery the cops were investigating, had no gun on him, and was 30 feet away with his back to Barron when the cop fired.

The judge ruled that Barron was entitled to qualified immunity, a legal doctrine meant to protect police and other government officials from frivolous lawsuits. A federal appeals court, saying the case “exemplifies an individual’s being in the wrong place at the wrong time,” upheld the lower court’s decision.

“You shoot me, paralyze me, put me in a nursing home, ruin everything, and I can’t get no type of compensation?” Collie said. He leaned back in his bed. “This ain’t justice.”

Video: A woman rescues a protester, who was knocked to the ground by a group of police officers!

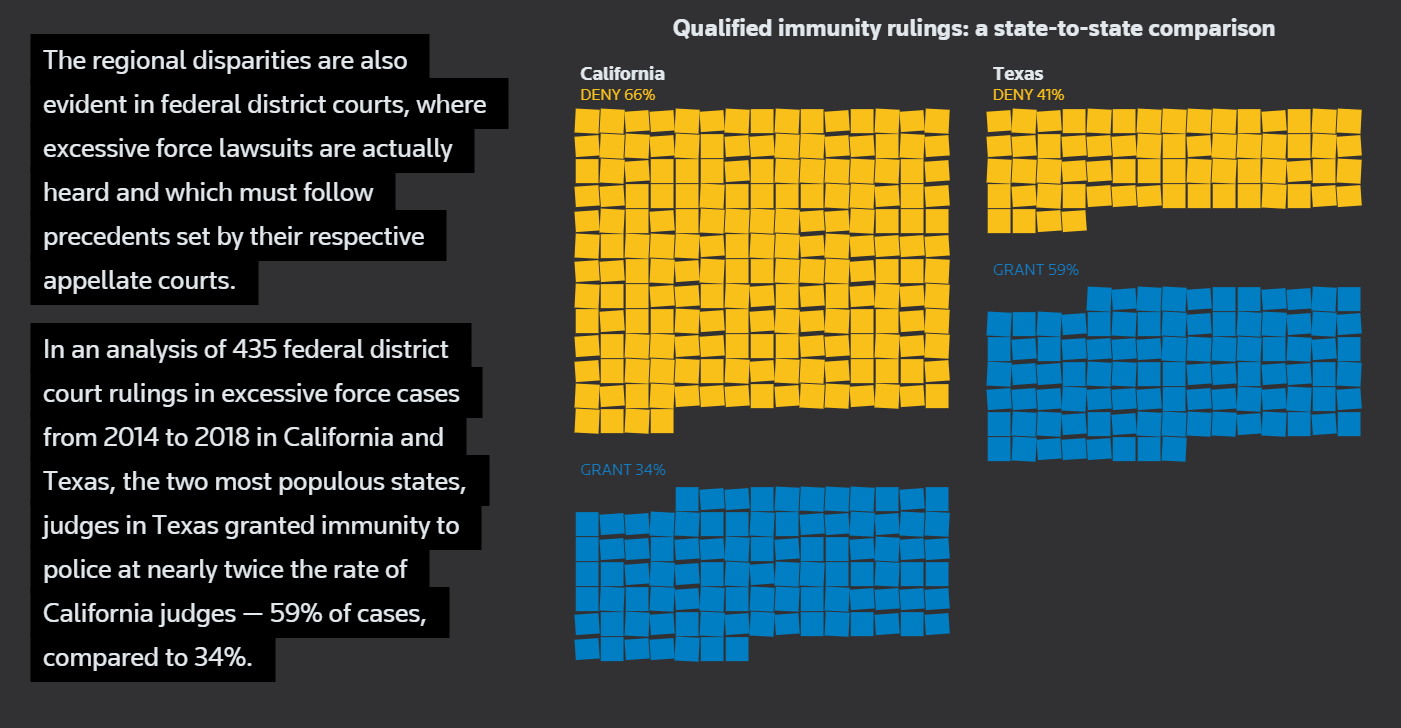

Collie would have stood a much better chance of getting the justice he sought if he had been able to sue elsewhere. That’s because, in excessive force lawsuits, courts in some parts of the United States are more likely to deny cops’ immunity than others.

In Texas David Collie was shot in the back as a possible suspect in a crime he didn’t commit.

The judge threw out Collie’s excessive force lawsuit, granting qualified immunity to the cop who shot him.

In California, an unarmed Benny Herrera was shot dead in an encounter with police after an ex-girlfriend reported he had struck her.

His family’s excessive force lawsuit was allowed to proceed after courts denied immunity to the cop who killed him.

For years, the words “qualified immunity” were seldom heard outside of legal and academic circles, where critics have long contended that the doctrine is unjust. But outrage over the killing of George Floyd and incidents like it have made this 50-year-old legal doctrine — created by the U.S. Supreme Court itself — a target of broad public demands for comprehensive reform to rein in police behavior.

The criticism that qualified immunity denies justice to victims of police brutality is well-founded. As Reuters reported just two weeks before Floyd’s death, the immunity defense has been making it easier for cops to kill or injure civilians with impunity. Based on federal appellate court records, the report showed, courts have been granting cops immunity at increasing rates in recent years — even when judges found the behavior so egregious that it violated a plaintiff’s civil rights — thanks largely to continual Supreme Court guidance that has favored police.

One of four Minneapolis police charged over Floyd’s death freed on bail

The regional differences Reuters has found in how qualified immunity is granted only add to arguments that the doctrine is unfair. “It’s essential to our system of government that access to justice should be the same in Dallas and Houston as in Phoenix and Las Vegas,” said Paul Hughes, a prominent civil rights attorney who frequently argues before the U.S. Supreme Court. “It shouldn’t turn on the happenstance of geography as to whether or not they (plaintiffs) have a remedy.”

The “happenstance of geography” shows up in a comparison of Collie’s case to the one Benny Herrera’s family filed after a cop killed him in 2011. Police in Tustin, California, was looking for the 31-year-old father of four after a former girlfriend reported that he had assaulted her. They found him walking along a lightly trafficked road, behaving erratically. As in Collie’s case, a cop opened fire when he thought Herrera was about to shoot him. Like Collie, Herrera did not have a gun.

In the Herrera family’s lawsuit, the cop was denied immunity. The district court judge, and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals after him, weighed the same question as to the courts in Collie’s case: Did the shooter act reasonably on fear for his and others’ safety when he used deadly force? In this instance, the court said no. The case could move forward.

Before the family’s lawsuit got to trial, the plaintiffs secured a $1.4 million settlement. Herrera always wanted his children to be financially secure, Elizabeth Landeros, mother of one of his children, said. They lost their father, she said, but at least “now they’ll be OK.”

Qualified immunity plays out differently from region to region because of differences in judicial philosophies among those regions, lawyers and legal experts said.

Over the years, the Supreme Court has repeatedly told lower courts to use an objective analysis when weighing police claims of immunity: They must determine whether the force used was reasonable or excessive, and if the latter, whether the specific type of force used has already been defined as illegal under “clearly established” precedent.

US police reform: Trump signs executive order on ‘best practice’

But how judges answer those questions is influenced by their personal views on police authority and individuals’ rights, and their views often reflect the cultural and political landscapes they inhabit. In typically conservative areas, judges tend to favor police, while in more liberal parts of the country, they tend to favor plaintiffs. Those tendencies get baked into circuit court precedents that all judges in that circuit must follow.

Most judges are from the area where they serve and grew up in that culture, and “whether they are liberal or conservative, they are bound to apply the law as it’s developed in that circuit,” said Karen Blum, a professor at Suffolk University Law School in Boston and a critic of qualified immunity. “Is it fair? No.”

The liberal-leaning 9th Circuit, where the Herrera family sued, has established in its precedents powerful support for plaintiffs. Among them are rulings cautioning against throwing out excessive force cases before a jury has had a chance to weigh an officer’s credibility, and requiring more than officers’ claims that they feared for their safety as grounds for granting immunity.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly rebuked the 9th Circuit for its willingness to deny cops immunity, and especially for applying, as the high court wrote in a 2011 ruling, “a high level of generality” when analyzing the question of clearly established precedent.

Reuters / Balkantimes.press

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.