Cartographer, navigator und captain: James Cook helped make the British Empire a world power. The Englishman first set foot on Australia’s east coast 250 years ago. It’s a piece of history with two perspectives.

A huge, mysterious continent was said to lie in the southern hemisphere, scholars wrote in the 18th century. They believed that as a counterpart to the European-Asian land mass, it was waiting for northern discoverers. Geographers theorized that its existence was necessary to steady the earth in its rotation. That assumption was driven by the desire, or the greed for knowledge, adventure, and most of all: for land.

The British Empire wanted to be the first to discover that mythical continent, fill the gaps on the world’s maps – and most of all, gain hegemony over the competing colonial powers Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands und France. In 1768, the Royal Society, a group of British scholars, exhorted the admiralty to take swift action. The chosen leader for the expedition was the experienced sailor and cartographer James Cook.

Spending the following ten years at sea in the service of the British crown, Cook went down in history for his discoveries. Over 35 locations bear his name, including two objects in space. But how did the man of humble background become one of history’s great discoverers?

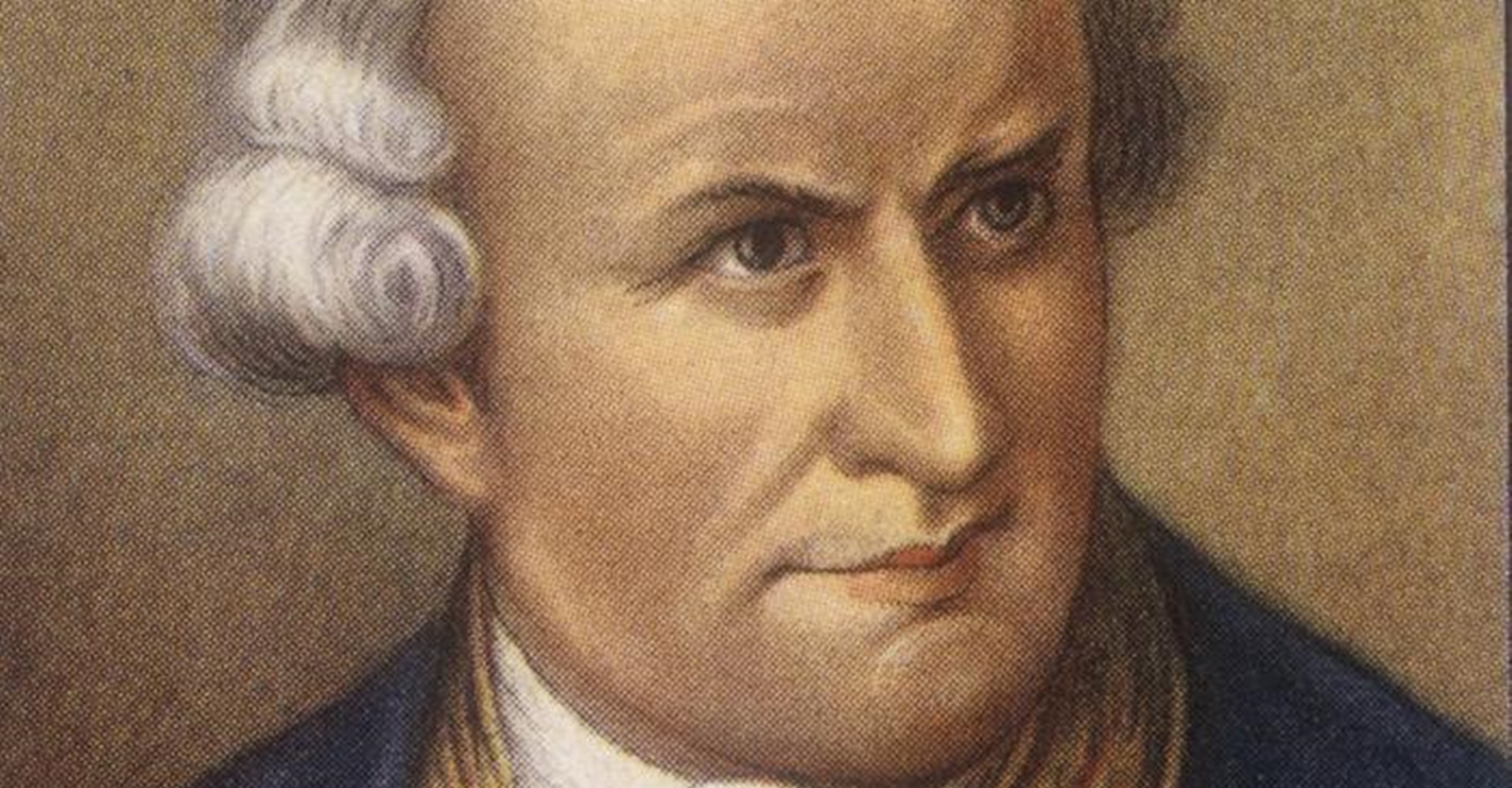

Who was James Cook?

Born the son of a daily laborer in the northeastern English community of Marton in 1728, James Cook and his many siblings grew up in poverty. It was only thanks to his father’s generous employer that he was able to attend the village school and learn reading and writing. A quick study, the boy was curious about everything.

At 18, he began his career in sailing on a coal transport ship: learning to steer, navigate and love the sea. He rejected the offer to become the ship captain however, his goal being the Royal Navy. In a few years there he demonstrated his exceptional talent for drawing maps in great detail, maps that helped the Royal Navy score military successes. James Cook was soon indispensable to the Crown, outshining nearly every other sailor in his knowledge and abilities.

So it was James Cook who on August 26, 1768 set forth from Plymouth with the Endeavour and headed south. The crew of 94 included botanists, drawers and zoologists – equipped with an array of technical equipment for an unusual expedition.

Secret mission

The Royal Society’s official commission was to observe the course of Venus in the Pacific, measuring the time the planet took on its course before the sun. With this data, scientists hoped to more precisely calculate the distance of the sun from the earth. The perfect point of observation was said to lie in Tahiti. Sailors knew about the southern Pacific island with its clear sky and where the sun remains over the horizon during the entire time that Venus crosses the sky. Equipped with four telescopes, James Cook was able to accomplish the Venus mission in June 1769.

Then began the secret part of the expedition, spelled out in a theretofore unopened envelope: discovery of the mythical southern continent.

The Endeavour took to sea on the far side of the 40th parallel. Navigating precisely, James Cook took the ship to New Zealand in a few months. He was not the first European to set foot there: about 150 earlier it had been visited by Dutch sailors. But Cook was the first to painstakingly cartograph the entire island. His measurements and drawings were so precise that they were used by captains until the 1950s.

Six months later the Endeavour headed north and hit the coast of New Holland, as Australia was then called. The outcome of James Cook’s next cartographic challenge: proof that there was no southern continent on a par with those in the North but that the southern hemisphere is largely ocean. In April 1770 Cook and his crew set anchor in what they christened Botany Bay, where the seafarers were fascinated by its then-unknown flora and fauna. Hungry for further discoveries, they proceeded further north to Possession Island, where Cook unilaterally claimed the land for the British Empire.

Two perspectives

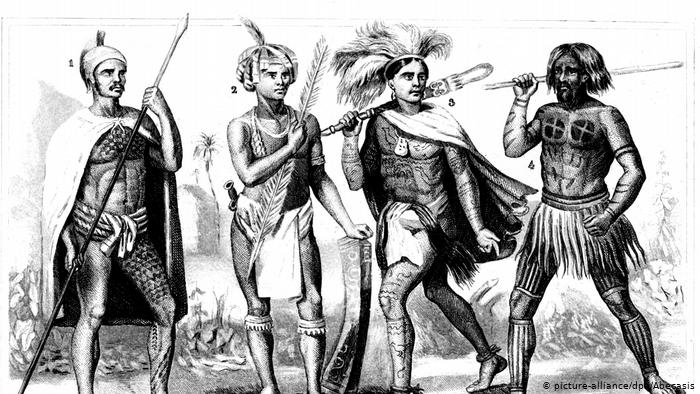

As triumphant and pioneering as the story of James Cook may seem from a scientific point of view, it can be seen from two perspectives – a British and a native Australian one.

When he dropped anchor back in his British homeland, James Cook was celebrated as a hero; even King George II offered his personal congratulations. The great explorer had not discovered the Australian continent per se, but he had conquered new lands for the British Crown. In the years to follow, British ships set sail for Australia and occupied the continent. Only eight years after Cook had staked his claim, the land was made a penal colony. That day in the calendar remains a national holiday for Australians.

In his diary, James Cook described the first encounter with the gweagal as one of aggression on the part of the latter. He recorded that one of the indigenous Australians threw a stone at him, and that men had hurled spears at his crew. The British were forced to use their firearms, wrote Cook – in self-defense.

In an article for the British Library, Dr. Shayne T. Williams, a gweagal representative, takes a different view of Cook’s arrival: “If you look at that same encounter from our perspective however, you see that two of the gweagal men were energetically fulfilling their spiritual duty to the land by protecting it from the presence of persons who were not entitled to be there. In our cultures it is not permitted to enter the land of a different culture without the necessary approval. Such an approval was always negotiated.”

James Cook therefore paved the way for the exploration of a country that didn’t want to be explored and for the conquering of a people who didn’t want to be conquered.

The discoveries of James Cook and their consequences are controversial today, but not his talent for cartography and his precise mastery of navigation.

DW / Balkantimes.press

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.