Refugees and migrants in Greece trying to reach western Europe have accused EU border protection agency Frontex of taking part in illegal deportations known as “pushbacks.”

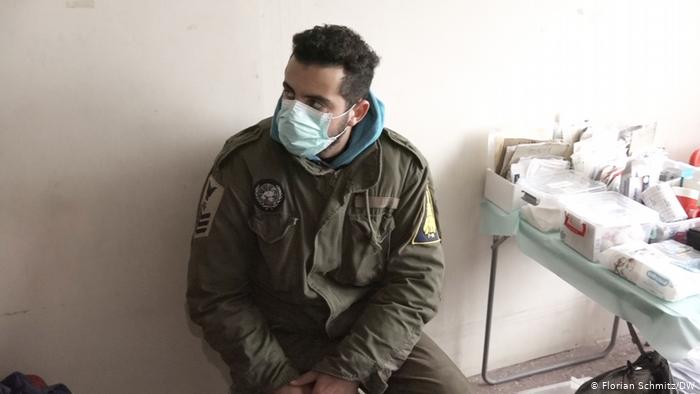

Ali al-Ebrahim fled in 2018 from Manbij, a Syrian city that was under Kurdish control, to escape being forced to fight in the conflict.

Al-Ebrahim, now 22, first tried his luck in Turkey. When he arrived in Antakya, not far from the Syrian border, Turkish authorities took his details and sent him back home without citing any reasons, the young Syrian man says in very good English. He explains that this meant he was banned from legally entering Turkey again for five years.

Nevertheless, al-Ebrahim decided to try again, this time with the aim of reaching Greece. He managed to make his way to Turkey’s Aegean coastline and eventually reached the Greek island of Leros in a rubber dinghy. When he applied for asylum, however, his application was rejected on the grounds that Turkey was a safe third country.

But al-Ebrahim was not able to return to Turkey, and certainly not Syria — though this was of no interest to Greek authorities. “The new Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis is very strict when it comes to migrants,” he says. “So I decided to go to Albania.”

Related Posts

Uniforms with the EU flag

Al-Ebrahim says that in September 2020, he traveled by bus with five others to the northern Greek city of Ioannina, and then walked to the Albanian border without encountering any Greek police.

But, he says, staff from the EU border protection agency Frontex stopped them in Albania and handed them over to Albanian authorities in the border town of Kakavia. When asked how he knew they were Frontex officials, al-Ebrahim replies, “I could tell from their armbands.”

Frontex staff wears light-blue armbands with the EU flag on them.

€5,000 to reach Austria

Al-Ebrahim says that he and the other migrants asked the Albanian authorities for asylum but were told that the coronavirus pandemic made it impossible to file any new asylum applications. They were then just sent back to Greece without the Greek authorities being notified, he says.

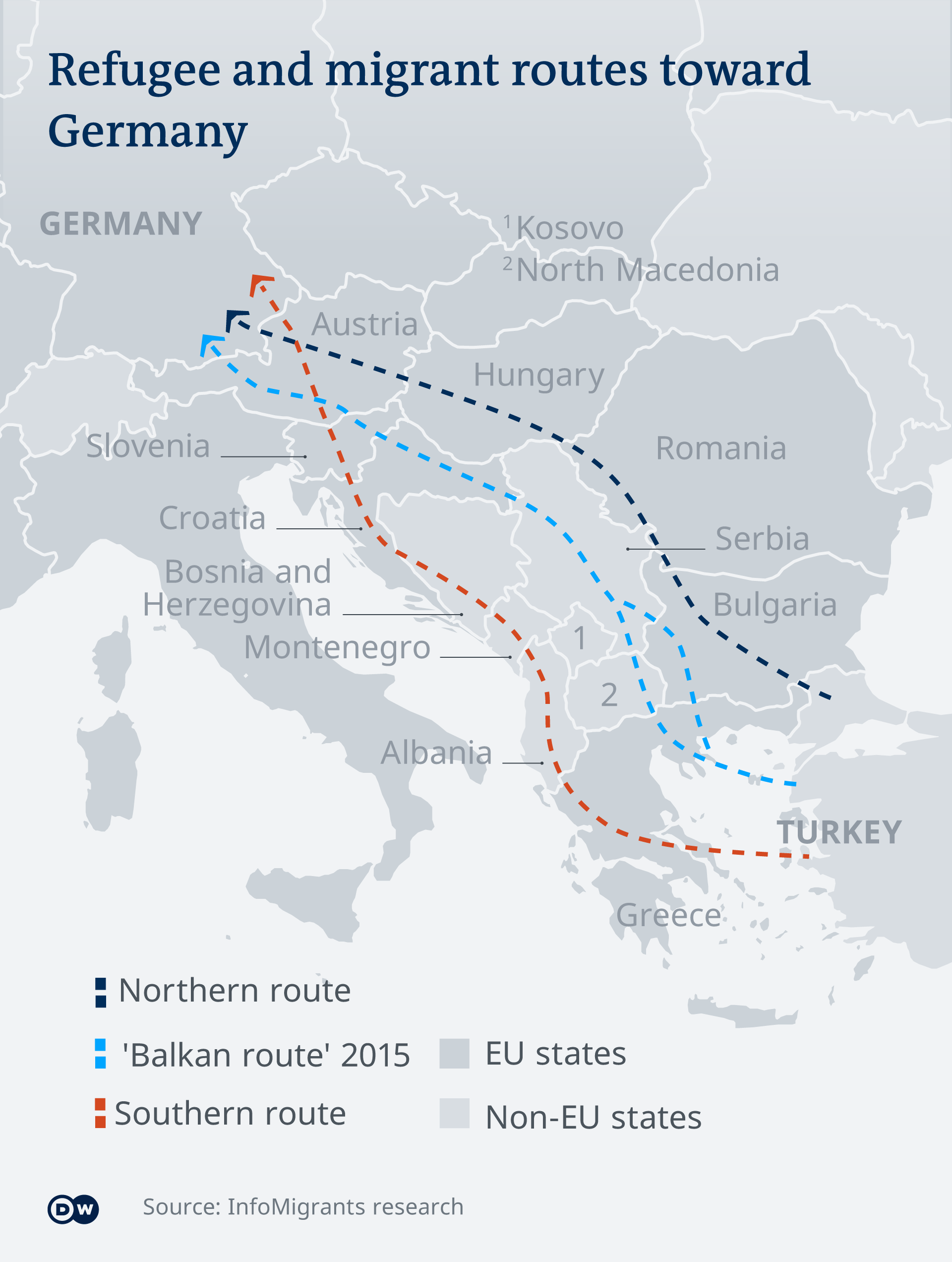

Al-Ebrahim had more luck on the second attempt. He managed to travel to the Albanian capital, Tirana, and then on to Serbia via Kosovo.

His interview takes place at a refugee camp in the Serbian city of Sombor, near the Hungarian border. Al-Ebrahim says he wants to travel on through Hungary into Austria, but the traffickers charge €5,000 to get as far as the Austrian border.

Detention instead of asylum

Hope Barker has heard many similar stories before. She coordinates the project “Wave – Thessaloniki,” which provides migrants traveling the Balkan route with food, medical care, and legal advice. Barker tells that the northern Greek city was a safe haven until the new conservative government took office in summer 2019.

In January 2020, a draconian new law came into effect in Greece. According to Barker, it allows authorities to detain asylum seekers for up to 18 months without reviewing their cases — and detention can then be extended for another 18 months.

“So you can be held in detention for three years without any action on your case if you ask for asylum,” says Baker.

Pushbacks by Frontex?

Baker tells that the illegal deportation of migrants, known as “pushbacks,” happens both at the borders and further inland. Migrants trying to reach western Europe avoid any contact with Greek authorities.

Refugee aid organizations say there have been “lots of pushbacks” at the border with North Macedonia and Albania. Baker says that witnesses have reported hearing those involved speaking German, for example, and seeing the EU insignia on their blue armbands.

Frontex rejects allegations

Baker says that it is, nonetheless, difficult to prove pushbacks at the Greek border because of the confusing situation, but she adds that they know that Frontex is active in Albania and that there are pushbacks on a daily basis across the River Evros that flows through Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey and forms a large part of the border. “We know that pushbacks are happening daily. So, to think that they don’t know or are not at all involved in those practices seems beyond belief,” says Baker.

A Frontex spokesman told that the agency had investigated some of the allegations and “found no credible evidence to support any of them.”

Frontex added that its staff was bound by a code of conduct, which explicitly calls for the “prevention of re filament and the upholding of human rights, all in line with the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.”

“We are fully committed to protecting fundamental rights,” it added.

Border protection from beyond the EU

So why does the European border protection agency protect an external border of the European Union from the Albanian side? “The main aim of the operation is to support border control, help tackle irregular migration, as well as cross-border crime, including migrant smuggling, trafficking in human beings and terrorism, and identify possible risks and threats related to security,” said Frontex.

Frontex also said that cooperation with countries in the western Balkans was one of its priorities. “The agency supports them in complying with EU standards and best practices in border management and security,” the spokesman said.

Yet it is worthwhile taking a look at another part of Greece’s border. While military and police officers are omnipresent at the Greek-Turkish border and are supported by Frontex staff, you seldom encounter any uniforms in the mountains between Greece and Albania. As a result, this route is regarded as safe by refugees and migrants who want to travel onward to western Europe via Greece.

The route west

Many migrants travel from Thessaloniki to the picturesque town of Kastoria, about 30 kilometers outside Albania. “There, the police pick us up from the bus and take us to the Albanian border,” Zakarias tells at the Wave Center in Thessaloniki. He is Moroccan and arrived in Greece via Turkey.

But at this point, these are just rumors.

That afternoon the men get on the bus. Another Moroccan man, 46-year-old Saleh Rosa, is among them. He has been in Greece for a year and was homeless for a long time in Thessaloniki. “Greece is a good country, but I cannot live here,” Rosa tells. He aims to reach western Europe via Albania, Kosovo, Serbia, and then Hungary.

Ominous police checks

Police stop the bus shortly before its arrival in Kastoria. There is a parked police car with uniformed officers. Two men in plain clothes board the bus, claiming to be police. Without showing any ID, they target the foreigners, detaining Saleh, Zakarias, and their companions.

At around 11 pm that same evening, the migrants send a WhatsApp message and their Google coordinates. They say that the men in plainclothes have taken them to a place some 15 kilometers from the Albanian border but within Greece. Later in the Albanian capital, Tirana, we met with Rosa again, who stresses that his papers were not checked in Greece.

Conflicting accounts

When asked, Greek police authorities confirmed the existence of the plain-clothed officers and the roadside check. But then their account diverges from that of the two men. Police said they wanted to check if the migrants were legally permitted to be in Greece and they were released once this was confirmed.

But the migrants say that Saleh Rosa was the only one with the papers to stay in Greece legally and that the other men were unregistered. Moreover, there is a curfew in Greece because of COVID-19. You are only allowed to travel from one district to another in exceptional cases. Even if they had been carrying papers, the men should have been fined.

DW / Balkantimes.press

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.