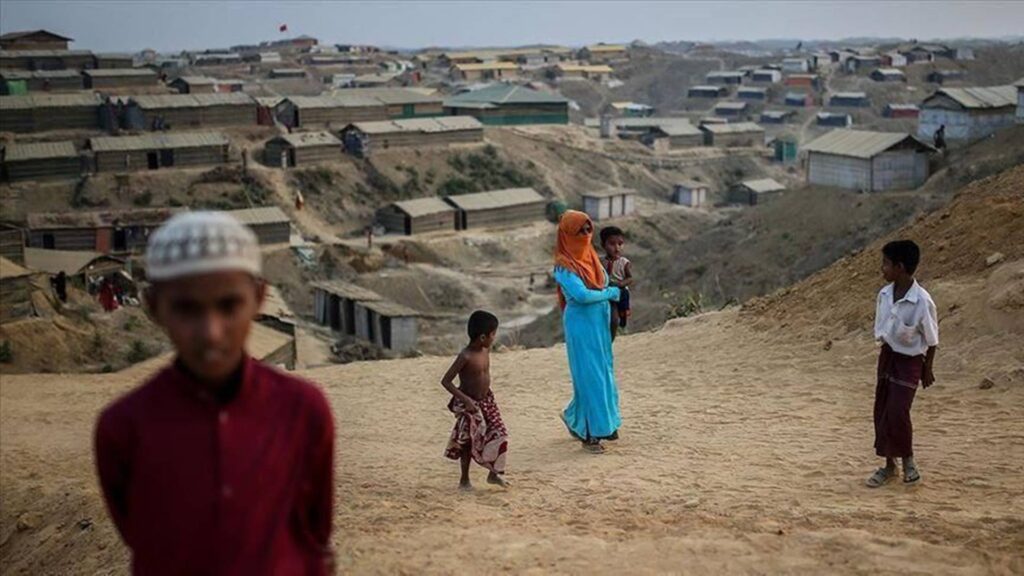

DHAKA, Bangladesh: 65,000 children at squalid camps in Myanmar’s Rakhine State are deprived of education, says Human Rights Watch

A US-based rights group has found Rohingya living at squalid camps in Myanmar’s Rakhine State at high risk of “long-term marginalization” and “segregation”.

A Human Rights Watch’s 169-page report — titled An Open Prison without End: Myanmar’s Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State, documents the inhuman conditions of approximately 130,000 Rohingya Muslims living in 24 camps or camp-like settings in central Rakhine since 2012.

The report is based on 60 interviews with Rohingya, Kaman Muslims, and humanitarian workers since late 2018.

“The Myanmar government has interned 130,000 Rohingya in inhuman conditions for 8 years, cut off from their homes, land, and livelihoods, with little hope that things will improve,” said Shayna Bauchner, Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report.

Underlining the deprivation of education as a violation of the fundamental rights of the 65,000 Rohingya children who have been growing up at the camps in Rakhine, the report said: “It serves as a tool of long-term marginalization and segregation of the Rohingya.”

Lack of education will also cut off the younger generations of Rohingya from “a future of self-reliance and dignity” and “the ability to reintegrate into the broader community.”

“Since childhood, I have lost many opportunities for my education. If I could have come [to Yangon] in 2005, I could have changed my life,” the report quoted a Rohingya woman, who has been barred from attending Sittwe University since 2012 for undefined “security” reasons.

She passed the matriculation exam to study in Yangon in 2005 but was never granted permission to leave Rakhine.

High rates of malnutrition

Camp detainees have also been suffering from “higher rates of malnutrition, waterborne illnesses, and child and maternal mortality than their ethnic Rakhine neighbors”.

“There is no chance to move freely […] We have nothing called freedom,” the report quoted a Rohingya man as saying.

Meanwhile, Rohingya at camps have been strictly restricted from working outside, resulting in “serious economic consequences,” the report added.

“Almost all Rohingya in the camps were forced to abandon their pre-2012 trades and occupations. Former teachers and shopkeepers have been left seeking ad hoc and inconsistent work as day laborers for an average of 3,000 [Myanmar] kyat (US$2) a day.”

An 18-year-old Rohingya from the Say Tha Mar Gyi camp said: “Some of us want to run our own businesses but we don’t have money to invest. Some of us want to be carpenters but we don’t have the tools. Some of us want to go fishing but we don’t have boats.”

The report also focused on the cycles of oppressions launched by the Myanmar authorities against the Rohingya Muslims for long.

“In the city of Sittwe, where about 75,000 Rohingya lived before 2012, only 4,000 remain,” it said, adding that surrounded by barbed wire, checkpoints, and armed police guards, they now live under “effective lockdown”.

Violence against Rohingya

Authorities used the 2012 violence against Rohingya communities as “a pretext to segregate and confine a population it had long sought to remove from the country”, the report said.

Referring to recent works of constructing permanent structures near the current camp locations by Myanmar authorities, the report warned of “further entrenching segregation and denying the Rohingya the right to return to their land, reconstruct their homes, regain work, and reintegrate into Myanmar society”.

“Ethnic cleansing and internment since 2012 laid the groundwork for the military’s mass atrocities in 2016 and 2017 in northern Rakhine State, which also amount to crimes against humanity, and possibly genocide,” it added.

According to Amnesty International, more than 750,000 Rohingya refugees, mostly women, and children, fled Myanmar and crossed into Bangladesh after Myanmar forces launched a crackdown on the minority Muslim community in August 2017, pushing the number of persecuted people in Bangladesh above 1.2 million.

Since Aug. 25, 2017, nearly 24,000 Rohingya Muslims have been killed by Myanmar’s state forces, according to a report by the Ontario International Development Agency (OIDA).

The report urges Myanmar’s San Suu Kyi government to immediately end the controversial 1982 Citizenship law and other arbitrary laws, policies, and practices that have resulted in “an apartheid regime against the Rohingya population”.

“Lift all arbitrary restrictions on freedom of movement for Rohingya, Kaman, and other minorities, and cease all official and unofficial practices that restrict their movement and livelihoods.”

Call for sanctions

Pointing to the basic humanitarian needs of the people in Rakhine, the report urged Myanmar to “grant humanitarian groups and UN agencies immediate, unrestricted, and sustained access to Rakhine State.”

It asked the UN to develop “a comprehensive, practical, and detailed approach to assistance provision in Rakhine State, centered on long-term solutions for displaced populations that prioritize human rights protection and avoid reinforcing segregation, discrimination, and persecution of Rohingya.”

The report also urged the international community and donors to “impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on officials and entities—in particular, military-owned enterprises and companies—that are credibly implicated in grave international crimes, including apartheid and persecution [against Rohingya]”.

Meanwhile, 19 human rights groups based in Myanmar on Thursday asked Myanmar to control all hate speeches ahead of the November general elections.

“Myanmar must tackle root causes of hate speech and address the impunity of perpetrators while ensuring that measures to combat hate speech are in line with international human rights standards with robust and inclusive participation of civil society”, they said in a joint report.

Underlining the “erosion of the rights of ethnic and religious minorities” across Myanmar, the report said: “There is persistent and unaddressed impunity for the perpetrators of hate speech, while journalists, human rights defenders (HRDs), activists and civil society organizations are targeted for exercising legitimate speech.”

“Too many of those criticizing the government and military have been thrown in jail under bogus charges. Without free speech, how can we advance democracy and human rights or adequately protect women’s rights,” said Pwint Phyu Latt, coordinator of Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement?

Related Posts

AA / Balkantimes.press