We rode every inch of it, from Manhattan to Buffalo to the Canadian border. This is what it was like.

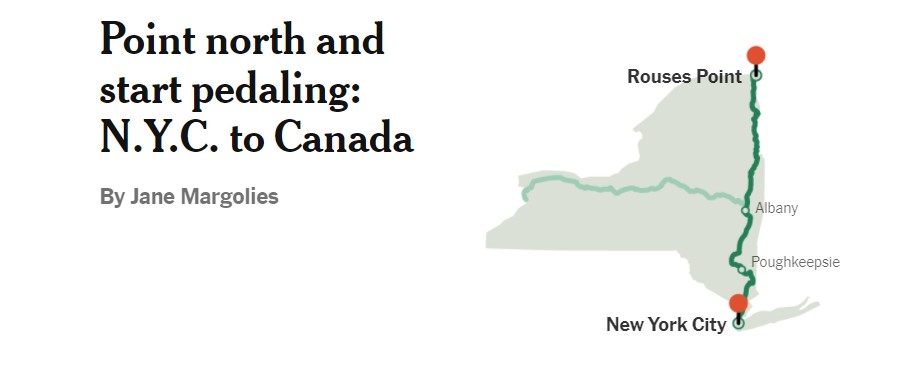

Last December, the Empire State Trail — a sprawling, 750-mile cyclist and pedestrian route that connects Buffalo to Albany and New York City to the Canadian border, forming what looks like a sideways T — opened to the public. Considering the pandemic bike boom, the timing was perfect.

About 400 miles of greenways, repurposed rail lines and bike paths already existed in New York. So, when the $200 million projects were announced in 2017, the state rushed to fill in the gaps between them.

Where new bike trails were not possible, blue-and-yellow signs were installed on roads signaling the way, and some guardrails were added to protect cyclists from vehicular traffic.

The result — a combination of protected paths, city streets, highway shoulders, and country roads that pass by small towns and cities — offers views of wetlands, waterways, grasslands, and mountain ranges. It is a showcase of New York State’s history and natural beauty.

Recently, two reporters set out on bikes to experience the trail for themselves. One traveled from Buffalo to Albany, and the other, from New York City to the Canadian border.

Here are the highlights.

The route: Lower Manhattan to Rouses Point

The north/south part of the trail, on the eastern side of the state, is not one bike route but many, each differing in length, type, surface material, and scenery, all stitched together.

If diversity is what you’re after, this trial’s for you.

The official website divides the whole 400-mile shebang into two main sections: the Hudson Valley Greenway Trail (N.Y.C. to Albany) and the Champlain Valley Trail (Albany to Canada). But on the ground, those categorizations are largely irrelevant; it’s the smaller trail segments that define the journey.

The approach

The concept of leaving my front door in New York City with my bike and, 400 miles later, arriving at the Canadian border, had definitely piqued my interest.

But I didn’t have a spare week to do the whole trail in one go. Plus, when I started plotting this trip back in April, I had yet to be vaccinated and trains and hotels still seemed risky. So I cooked up a crazy scheme, made possible because I have a car, a bike rack, and a very understanding husband.

The plan: Whenever my husband and I had a free day, we would hitch our bikes to our car and drive to the section of the trail I’d last completed. I’d start pedaling while my husband drove to the day’s destination, parked, and sometimes biked back to meet me.

After I’d completed my jaunt, we’d head home and, yeah, I do cringe at the environmental impact of all that driving.

City greenway, Bronx-bound

My first day, however, was car-free. On April 30, I started at a kiosk in Battery Park City at the bottom of Manhattan, which serves as the gateway to the Empire State Trail. It has a map and one of those “you are here” arrows at this southernmost point — which kind of throws down the gauntlet.

From there, I started pedaling north on the Hudson River Greenway.

I knew this 13-mile protected path intimately. Many cyclists depend on it as an efficient alternative to Manhattan’s traffic-choked streets. Said to be the busiest bike path in the nation, it’s usually teeming.

In Upper Manhattan, the greenway ends at Dyckman Street, and a little urban adventure — complete with iffy signage and rutted roads — begins. Beware of the dangerous Broadway Bridge entering the Bronx, and have fun when the trail takes you onto the sidewalk (seriously?) of the Manhattan College campus.

New York’s Stonehenge and quirky birdhouses

The city portion of the Empire State Trail concludes in Van Cortlandt Park, on the new and splendid, if short, Putnam Greenway. This path, which opened last fall, follows the Putnam Division of the old New York Central railroad, which operated until 1958.

I passed 18-acre Van Cortlandt Lake and the curiosity known as the Grand Central Stones, a row of pillars that some have described as an urban Stonehenge. In fact, these are quarry samples that were under consideration when Grand Central Terminal was being built in Midtown Manhattan in the early 1900s.

The Putnam flows into Westchester’s South County Trailway, where construction of a different sort caught my eye in Hastings-on-Hudson: whimsical wooden birdhouses hanging from trees. Steve Pucillo, a local retiree, makes them.

On the North County Trailway, which came next, homeowners whose properties border the bike path had built wooden boardwalks, ladders, and even paths made from carpet remnants connecting their land to the trail.

After 40 or so miles and deep into Westchester County, I turned around and pedaled home.

Easy, pretty and smooth: The Maybrook Trailway

In May, I resumed my journey through Westchester. In Putnam County, I picked up the Maybrook Trailway in Brewster.

The 24-mile section opened in January, and there’s nothing quite like riding on asphalt that is still perfectly smooth, before tree roots and seasonal freeze-and-thaw cycles cause the paving to buckle. The trail is essentially flat, following part of a former freight rail corridor.

It passes wetlands, a couple of small waterfalls, and, at a spot where the Appalachian Trail crosses the Empire State Trail, a bridge over a stream that is a nice place to pause, enveloped in the sound of rushing water.

Peek-a-boo with the Hudson

The trail crosses New York’s famous river four times, as the waterway goes from mighty in Manhattan to quite modest near its origin in the north.

The most dramatic crossing is the Walkway over the Hudson. This wide 1.5-mile trail way, built on a historic railroad bridge from Poughkeepsie to the town of Lloyd, is more than 200 feet above the water’s surface.

From old brickyards to open roads

I arranged to meet Andy Beers, the Empire State Trail director, in New Paltz to ride the Wallkill Valley Rail Trail. He told me about the scramble to install thousands of signs across the state (admitting to stashing some in his car so he could hop out and hammer one in on the spot). We passed the charming Rail Trail Café (wood-fired pizza, kale drinks) and old limestone caves, ending up at Kingston’s new Hudson River Brickyard Trail, which will eventually be part of a new state park on 520 riverfront acres that will include the ruins of brickyards.

At the next Hudson crossing, on the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge, the view was impressive, but the busy bridge’s bike lane was entirely unprotected. Much of the Kingston-to-Hudson stretch is on-road — a taste of what I would increasingly encounter.

In fact, roads make up 55 percent of the trail heading south to north, but open roads do let you take in more of your surroundings; on the rail trails, you often can’t see beyond the dense greenery. I got so caught up ogling the historic houses on a country road in Dutchess County that I missed a sign around Bard College, and it took me a while to find the newly upgraded trail through the Tivoli Bays Wildlife Management Area.

A trolley line with a textiles past

Another day, another fantastic tail. The 36-mile Albany-Hudson Electric Trail, between Hudson and Rensselaer, opened last December on a route where a trolley ran from 1900 to 1929. Several old depots still stand.

Much of the Electric Trail is paved with stone dust — finely crushed, compacted gravel that my road bike had no trouble handling — interspersed with asphalt.

The country road sections pass through small hamlets and wind past the ruins of old mills. This area was a major textile producer for decades, and the same creeks and waterfalls that provided water power for the trolley line also fueled the manufacture of cotton and wool.

Americana redux: shops and sites along the trolley trail

It was tempting to keep sailing along, but I stopped to check out local businesses.

Velo Domestique, a new bike shop in Valatie that opened in a 1990s carwash, has a cool relic of cycling’s early days: a set of huge old wooden rollers, which allow for indoor training on outdoor bicycles. The rollers were previously owned by a motorcycle officer and sometimes cyclist who is said to have once pulled over Babe Ruth for speeding.

Farther north, Smiles Soft Serve Ice Cream, a family-run frozen custard stand in Nassau, installed a bike rack and recently added a porta-potty that the owners rented to save their septic system because of so many cyclists passing through.

And Samascott Orchards in Kinderhook rang a bell for me because its apples are sold at the city’s Greenmarkets.

A city looms on the horizon

By the time the buildings of Albany rose up in the distance, it was good to see a city again. But the route skirts the capital, continuing on the Mohawk-Hudson Bike-Hike Trail, the river on my right already narrower and more placid.

Farther north, there were a few tranquil trails made from old canal towpaths, along with still-active canal locks and lovely Lake Champlain.

Much of the Champlain Valley Trail follows old New York State Bike Route 9, which meant mile after mile of on-road riding, sometimes on the crumbling shoulders of 55-mile-an-hour roads. In the Adirondacks, State Route 22, north of Willsboro, wound to an elevation of nearly 1,000 feet. The ride was made all the more challenging by a skimpy road shoulder and trucks zooming by.

In Keeseville, the road leveled out. But I saw so few cyclists, I found myself waving like a maniac whenever I encountered someone on two wheels.

The final push to Canada

By this time it was June, Covid had momentarily receded as a threat, and I was able to piece together a few consecutive days to wrap up the journey. I biked by day, my husband and I stayed at Airbnbs by night, and, for our final stop, we pitched a tent at Ausable Point Campground on Lake Champlain, which put me less than 40 miles from Rouses Point, a village on the American/Canadian border, with flags from both countries flying from lampposts. I reached the border the following morning and saw the kiosk map with its “you are here” arrow, this time at the top of the trail.

I’d officially become an end-to-ender.

My advice

I doggedly covered every mile in the interests of journalism, but the 80 miles in the Adirondacks between Whitehall and Keeseville are not for everyone. You need to be physically fit to handle the hills, and you have to have nerves of steel to cope with the noise and proximity of the trucks.

For mostly stress-free riding, stick to the Hudson Valley Greenway Trail, the route’s southern half, where day-trip options abound. For an overnight, consider Kingston or Hudson as midpoints.

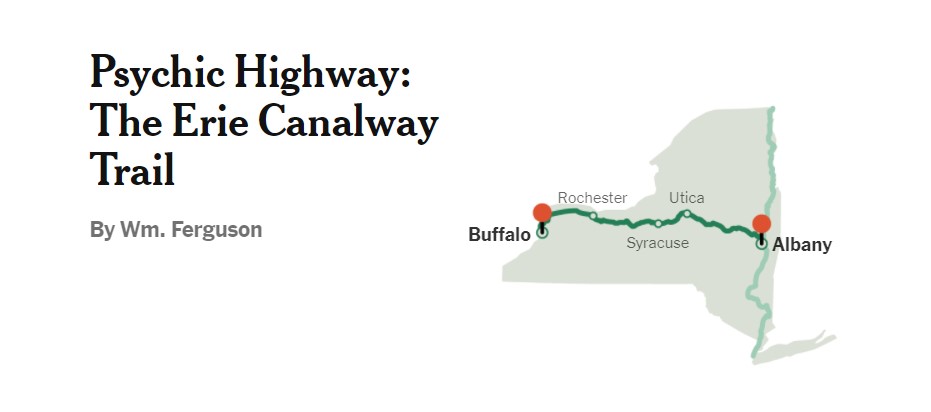

The route: Buffalo to Albany

Dotted with canalside towns that tell a rich and often strange history of the westward expansion of America, the Erie Canalway Trail, a 360-mile bike path connecting Buffalo to Albany, is a route to savor. One endurance cyclist I spoke with made it from end to end in just over 31 hours (stopping only to stretch, eat and fix a flat), which is impressive. But racing through this trail defeats its purpose.

The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, not only opened up the nation to commerce, it also was a kind of psychic highway that attracted a steady stream of 19th-century freethinkers: Abolitionists, Mormons, Spiritualists, Adventists, and suffragists can all trace their roots to this fertile vein of New York State.

The towns along the path, which are much more established than their north/south counterpart, can hardly be glimpsed from the interstate and are very welcoming to cyclists.

The approach

If you live in New York City, the Erie Canalway isn’t easy to get to. I have family in Buffalo, so I could start there. Along with my 22-year-old son, we planned a week to ride to Albany, where we had left his car, and then to drive home to Brooklyn.

I highly recommend sharing the trail with a physically fit young person who is happy to bear half the camping gear and is eager to ride in front and let you draft in his slipstream.

Cycling is relatively easy. Eighty-five percent of it is on a dedicated bike path, most of which is flat and is either paved or made of crushed stone. The towns are never much more than 20 miles apart, so it’s simple enough to ride to a hotel every night.

There are a few state parks not far from the trail where you might pitch a tent, but we had planned to “wild camp” at the locks along the canal. These are first-come, first-served hiker-biker-boater sites. But as we pedaled past the locks in the early part of the ride, it was hard to tell: Were these well-tended lawns meant for public camping? Right next to the path? It turns out yes.

I spoke with Robin Dropkin, the executive director of Parks & Trails New York, and the woman behind the indispensable map and guidebook “Cycling the Erie Canal.” She confirmed that these were the suggested campsites, but she also agreed with my hesitancy. “They are a little exposed,” she said.

It felt like camping in Central Park. Despite having loaded our bikes with a tent, sleeping bags, and cooking gear, we mostly stuck to hotels.

Points of entry

Buffalo is a fantastic city. It had electric lights years before Paris. But if you’re only going to use Buffalo as a starting point, consider beginning farther down the road. There are a few lovely miles along the shore of Lake Erie, but the trail here is a patchwork of poorly marked sidewalks, multipurpose paths, and aggravating detours.

If you’re not a completist, maybe start at North Tonawanda. This is really where the Erie Canalway begins in earnest. In fact, you could do worse than beginning your ride in Pendleton, a few miles down the path and home to Uncle G’s, the first of many excellent ice cream parlors suspiciously close to the bike trail.

We brake for honey

Medina doesn’t look like much from across the canal, but it’s a wonderfully preserved town that once made its fortune from Medina sandstone, used worldwide (the Brooklyn Bridge, Buckingham Palace) until the 1930s. Hart House, a boutique hotel that occupies one floor of a former shirt manufacturer, seems eager to court cyclists (our room was decorated with an enormous Schwinn medallion and nicknamed the Brake Pad). On the ground floor is Meadworks, an actual meadery that makes and sells artisanal honey wine, which is served in a rustic-chic bar or in the outdoor “Biergarten.”

Engineering feats: locks and tunnels

There is a number of impressive structures along the canal. The “flight of five” locks in Lockport is considered an engineering marvel; it allowed barges to rise in five separate chambers as if on an escalator over the Niagara Escarpment. The Nine-Mile Creek Aqueduct outside of Camillus is the last of 32 working aqueducts. The enormous UTICA tower that emerges without warning in a lonely field is kind of a thrilling moment in a monotonous stretch.

But only one attraction will elicit a visceral response from the nonengineer. Around Knowlesville, you can scramble down a hill to wander into the only tunnel to pass under the Erie Canal. It is wondrous and alarming to stand in this echo chamber, which is clearly dripping a lot of canal water.

Take the detour

The Parks and Trails guidebook offers a few alternate routes away from the canal. Around Clyde, it suggests a detour south to Seneca Falls, past Cayuga Lake, and rejoining the canal after a trip through the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge. Take the detour.

Once you have left the trail and endured a short, sketchy ride on the shoulder of a busy highway, you enter miles of bucolic country lanes. We didn’t encounter a single vehicle for more than 90 minutes as we passed through Amish farmland and field upon field of sunflowers.

Seneca, not Bedford Falls

Seneca Falls simultaneously tries to honor competing pasts. It is the birthplace of the women’s rights movement, dating to the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848, which is commemorated by the Women’s Rights National Historical Park and the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

It is also the inspiration for “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

There is a museum dedicated to the movie (Seneca Falls stood in for Bedford Falls), but really all you need is to stroll the truss bridge and imagine George Bailey contemplating hurling himself into the waters below.

We booked a room at the Gould, another boutique hotel. The staff was wonderful, although our room had so much chrome and filigree it looked like the apartment of a drug lord in Grand Theft Auto. Still, the hotel let us store our filthy bikes in a conference room.

For dinner, the concierge suggested we make a reservation for Sackett’s Table. Reservations? On a Tuesday night in Seneca Falls? In the middle of a pandemic?

In fact, the place was booked, and it deserved to be. Sackett’s Table is an artisanal butcher attached to a restaurant, a farm-to-table experiment in a valley of brewpubs.

The menu is Haute comfort food: duck nuggets, deconstructed fried chicken, braised beef ravioli. But there’s also a butcher’s case filled with locally sourced meats. You point out the cut — that pork tenderloin, say, or that beef flank — and they’ll prepare it to order. Best meal of the tour, without question.

Camping, finally

Determined to make use of the many pounds of camping gear we carried, we made for Green Lakes State Park. We had nearly 60 miles ahead of us, but we had to get through Syracuse first. We had been alerted to the terrible state of cycling there. Adventure biking forums were filled with dire warnings about unfriendly city streets and how easy it was to get lost.

But this was before a $36 million, 14-mile extension passing through the city was completed last year. The new bike path runs right through a rundown stretch of strip malls and muffler shops. But it’s nicely landscaped, and the ride feels like a gentle luge runs through an urban highway. Is this what those Danish bicycle superhighways feel like?

Before we knew it, we were back in nature and climbing a steep ridge into the state park.

Rain happens

Fortified by our night in the campground, we had intended to spend the next night in the tent. But we got off to a slow start when we realized that the bolt securing my son’s pannier rack had sheared right off. It is truly amazing what you can achieve with a full roll of electrical tape and 45 minutes of profanity.

Then it started raining, just as the trail put us on a two-lane highway for 10 miserable miles. We rejoined the bike path in Ilion, sheltering at a hot dog joint adjacent to a marina along the Mohawk River. Was the grilled frankfurter at Voss’s truly the best I’d ever had? Quite possibly. But it still wasn’t a reason to pitch a tent in the freezing rain next to the marina. We rode a bit longer until Little Falls and decided to check into the somewhat pompous-sounding Inn at Stone Mill.

What a stroke of luck. The hotel was part of a massive 19th-century building, and the manager had no problem allowing us to roll our sopping wet selves (and our bikes) into our room, which had a grand view of the Mohawk River and the rocky promontory of Moss Island. On the ground floor was a terrific wood-fired pizzeria. Close by was a microbrewery in a converted garage that was equally hospitable to dogs and bluegrass musicians. A perfect end to a challenging day.

To the ramparts!

We wanted to spend a little time wandering along nearby Moss Island, which has some world-class rock climbing in the middle of the Mohawk River. So instead of pushing through to Albany, we spent the last night in Amsterdam, largely because there is a hotel there that looks like a castle.

The Amsterdam Castle Hotel did not disappoint. A former armory, the castle sits on a hilltop. Where the town is tidy and unassuming, the Castle Hotel is a riot of incongruous suits of armor, random medieval weaponry, mismatched and highly ornate furniture, and photocopied portraits of lords and ladies in gilded frames.

It is nutty and wonderful. And if you happen to be in town on a Friday, I highly recommend the fish fry at Shorty’s Southside Tavern, the polar opposite experience on the fancy axis.

Homeward bound

My son and I had grown a little weary of each other after six days. It happens. But the rolling hills leading into Schenectady and the well-groomed paths outside of Albany inspire a kind of Zen state. And when my annoyance subsided and I slowed down and let him catch me, we both had to smile at the beauty of an endless ribbon of the bike trail.

My advice

If you want to finish the trail in a week, expect to ride a little more than 50 miles a day. It sounds like a lot, but once you’ve done a day or two of that distance, four or five more feels like no big deal. Even at a leisurely pace of 10 miles an hour, you’ve got maybe five hours in the saddle every day, with time for lunch and a snack break. Also worth bearing in mind: Heading east from Buffalo toward Albany means you’ll be going downhill overall, and the prevailing winds will be at your back.

Planning your trip

The official Empire State Trail website is a good resource; it just added GPS to its map and will soon include lodging ideas, Mr. Beers said. Come spring, there will be a trip-planning guidebook.

For day trips, consider reaching your departure point by train. Much of the trail is reachable on Metro-North and Amtrak, and they’ve been making it easier for cyclists to hop aboard.

As of this fall, it is no longer necessary to have a bike permit to get on Metro-North. On weekdays, four bikes per train are allowed; on weekends, eight. You can also check timetables for bicycle trains — look for a bike symbol and a plus sign — these can accommodate up to 44 bikes on off-peak hours, perfect for group rides.

Amtrak’s carry-on service costs $20 and requires advance reservations, although some cyclists have had success as walk-ons. Train cars marked with a sticker have bike racks.

If you are driving and doing the trip with a group, consider organizing your own “sag wagon.” Ride with a group of three or more cyclists. Every day, someone takes a turn and drives the car ahead to that day’s destination. The designated driver can either tour the town or ride halfway back and meet the group.

Lodging and dining

Unlike many bike trails, the Empire is never far from civilization. You could certainly pack all your food and a tent and rarely need to pull out your wallet. But you could just as easily rely on hotels and restaurants. Most will opt for a middle path. And it’s worth considering Warmshowers, a network for traveling cyclists that offers free lodging to members.

Do I need a special bike? Should I do this?

Pretty much any bicycle that you feel comfortable riding for more than a few hours at a time will be fine on most of the trail, and cyclists of all levels of fitness will find most of the riding doable. That said, flat-bar handlebars have fewer hand positions and become tiring on long rides or multiday trips. Carbon-fiber road bikes with narrow wheels will find the occasional passage through gravel or mud difficult to navigate. Check with an outfitter like REI or the Brooklyn-based 718 Cyclery & Outdoors to see what kind of racks and bags your bike can handle. The more rugged sections of the trail are best done on wider tires, and if you’re heading into the Adirondacks, you’ll definitely want some gears.

The Empire State Trail is about as close to biking bliss as you can get in one of the least bike-friendly regions of the country, and while it’s an achievement to have ridden from the Battery to the border or from Buffalo to Albany, any time on two wheels among its many peaceable corridors is well worth it.

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.