The race to determine the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s next president — and by default, the next prime minister — will officially begin Tuesday, following Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s bombshell announcement last month that he will step down due to poor health.

Three candidates have thrown their hats into the ring.

Having secured backing from most major factions within the LDP, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga is widely predicted to be a shoo-in for the presidential election, but LDP policy chief Fumio Kishida and former Defense Minister Shigeru Ishiba are also in the running.

Japan’s Suga signals ultra-easy monetary policy to continue

Here’s a closer look at the three candidates vying to become party president in the Sept. 14 election.

Yoshihide Suga

For someone who touts continuity as one of his biggest selling points, Suga, as a politician, seems to have little in common with Abe, the political blue-blood whose policies Suga has vowed to inherit.

Unlike Abe and most LDP leaders over the last three decades, the 71-year-old Akita native prides himself on having navigated his way through the treacherous world of Japanese politics from scratch, without the privileges of a hereditary politician or the career-long tutelage of an internal faction.

Can-Do Attitude Took Yoshihide Suga From Strawberry Fields to Japan’s Pinnacle

Born into a family of farmers in Akita Prefecture in 1948, Suga left for Tokyo after graduating from high school and wound up working for a cardboard factory in Itabashi Ward.

He worked several different jobs part-time until he could eke out the money he needed to enroll himself at Hosei University — the cheapest private university he could find at the time — graduating in 1973.

In 1987, after an 11-year stint working as a secretary for the late trade minister Hikosaburo Okonogi, Suga debuted as a politician when he successfully ran as an assemblyman in Yokohama. He went on to make forays into national politics as a Lower House lawmaker in 1996.

Before his rise as a potential successor to Abe, his political career seemed to have culminated with his status as the nation’s longest-serving chief Cabinet secretary — the top government spokesman — under the Abe administration.

Often unsmiling and taciturn, Suga has seldom exuded the kind of charm sometimes seen from Abe, but he excelled at his job partly because he kept a tight rein on the nation’s bureaucrats.

Berkshire Hathaway Buys Stakes Valued at $6 Billion in Five Japanese Companies

As was the case during his time as an internal affairs minister, from 2006 to 2007, he deftly brandished power over personnel, using the threat of demotion or sacking to make bureaucrats obey government policies.

This tactic was exemplified by the initiative Suga took in establishing the Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs in 2014, which paved the way for the prime minister to appoint, at his own discretion, a significant number of elite bureaucrats at ministries and agencies of the central government.

Suga has thus grown adept at coordinating domestic affairs and overseeing crisis management at home, but one area that’s sorely missing from his resume is diplomacy.

His trips to Washington last year — which saw him meet with U.S. Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo — were widely hailed as his diplomatic “debut,” but his affinity for the international stage largely remains a mystery.

Unlike Abe, who has professed his ardent desire to revise the nation’s postwar, pacifist Constitution, Suga has rarely expressed a fixation on any political ideology or detailed grand visions for a national identity. Instead, he seems more driven by populist-style policies aimed at courting the public, such as boosting inbound tourism, slashing mobile phone bills, and initiating the furusato nōzei (hometown tax donation) program.

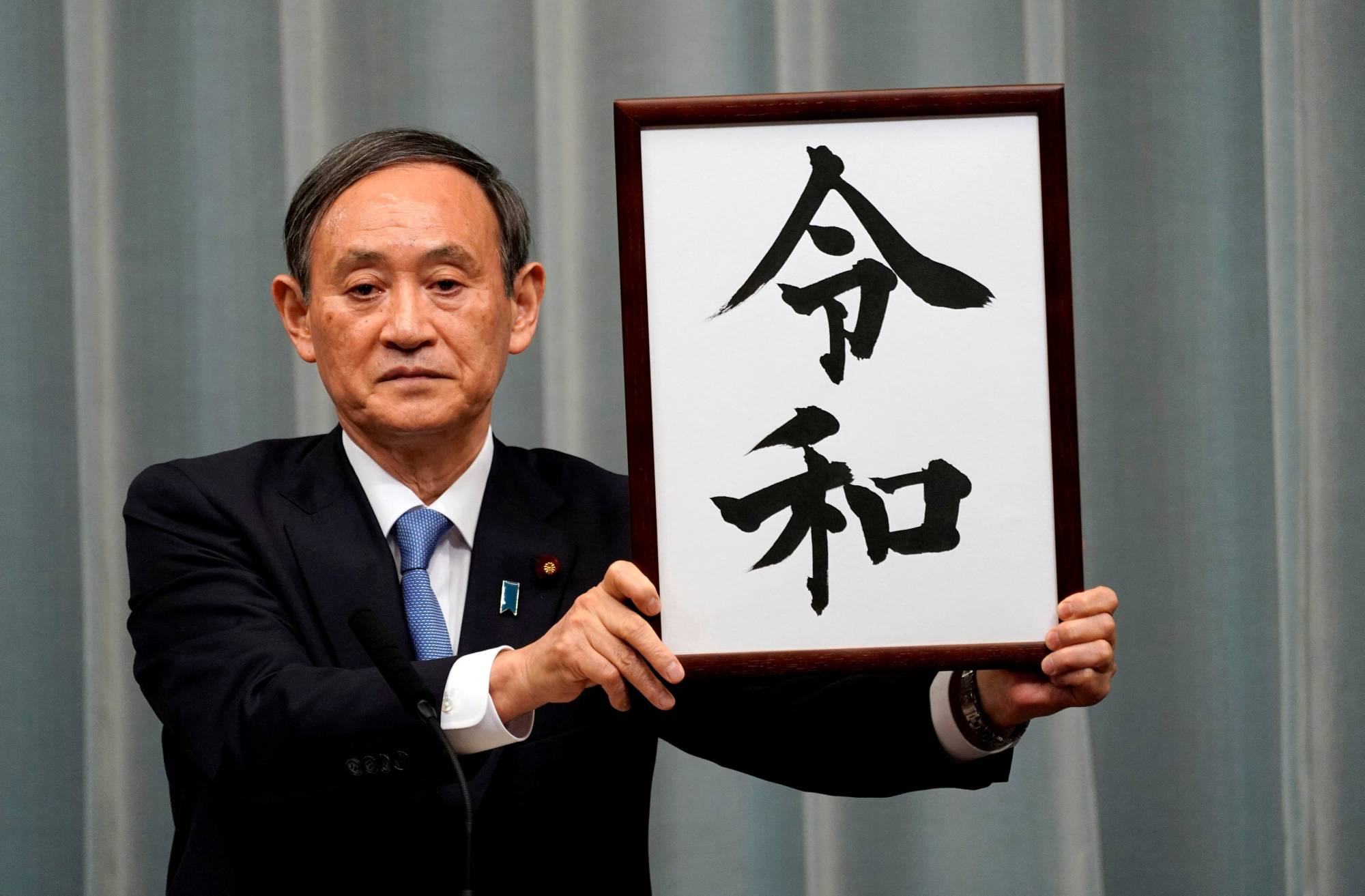

As chief Cabinet secretary, Suga enjoyed a surge in popularity in April last year when he unveiled the name of the new imperial era, Reiwa, gaining the nickname “Uncle Reiwa.”

But that avuncular image was in stark contrast with the brusque, sometimes the heavy-handed way he often conducts his twice-daily briefings, where he rarely goes off script and makes no secret of his disdain for reporters with critical questions — a coldness that has won him another title: “Teppeki,” or “the Iron Wall.”

Japan calls for G7 coordination to spur global growth, combat pandemic, finance minister Aso says

Fumio Kishida

Kishida has been called many things, including a “prince,” “elite” and a “loyalist.” But “fighter” has never been one of them.

In what is shaping up to be a make-or-break moment in his career, Kishida is now seeking to shed his image as a “politician who doesn’t fight” — by declaring candidacy for a leadership race he knows he has little chance of winning.

Head of the dovish, 47-member Kochikai faction of the LDP, Kishida the “prince” — a nickname his electoral office in Hiroshima says derives from good looks in his youth — has never quite been on the same page, ideologically, as political hawk Abe.

But by avoiding confrontation with Abe, Kishida, 63, is said to have long been working toward a shot at the role of the prime minister, in the hope that Abe would reward Kishida for his docility by nominating him as successor upon retirement.

Japan, Britain to protect encryption keys in trade pact, Nikkei says

It’s a double-edged tactic that on one hand has earned him a reputation as an Abe loyalist, but on the other made him appear passive and devoid of fighting spirit.

In the end, that smooth transfer of power from Abe to Kishida never materialized, with Abe essentially refusing to endorse him in the race.

One of the highlights of Kishida’s career is his tenure as foreign minister under the Abe Cabinet from 2012 to 2017.

As foreign affairs chief, the former banker carved out a solid reputation as a “man who gets the job done,” overseeing the landmark deal inked in 2015 with South Korea intended to resolve the issue of “comfort women,” who suffered under Japan’s military brothel system before and during World War II, and the historic visit in 2016 by then-U.S. President Barack Obama to the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.

In a 2017 Cabinet reshuffle, Kishida was then appointed as the LDP’s policy chief — a post he continues to hold today.

Known to be a hardened drinker, during a diplomatic dinner in 2013, Kishida dared his Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov to guzzle down cup after cup of sake he had brought from his electoral constituency of Hiroshima, going toe-to-toe with him in what eventually turned into a three-hour drinking match, according to a quarterly magazine published by his office.

Apple App Store draws fresh scrutiny in Japan, the epicenter of gaming

The political blue-blood, whose father and grandfather were Lower House lawmakers, is also known for his low-key ways, including a reticence that leaves little room for reporters to find fault with his comments.

But his reliability as a politician has failed to translate into public support, with media surveys routinely showing he is outranked by his rivals in public opinion polls on who should be the next prime minister.

Reports say Abe kept waiting for Kishida to start displaying more charisma so that, if he were elected prime minister, Kishida would be able to steer the LDP as its leader in national elections. But that transformation from self-effacing yes man into a strong leadership figure never came.

In fact, Kishida’s political acumen and negotiation skills came under scrutiny earlier this year. As LDP policy chief, Kishida reportedly spearheaded a proposal to distribute a ¥300,000-stimulus package to pandemic-hit households but gave up after he failed to coalesce his party around the plan.

‘Fortnite’ Fans Are Pushed to Choose Sides in Epic’s Legal Spat With Apple, Google

His blunders continued when a recent photo he shared on Twitter of himself and his wife relaxing at home — a promotional shot he evidently hoped would better portray his softer side — drew criticism that he had made his wife look more like a maid.

Shigeru Ishiba

Ishiba, 63, sets himself apart from the other two candidates by presenting himself as an outspoken critic of Abe — a risky tactic on which he has staked his political career over several years.

One of Ishiba’s most memorable confrontations with Abe was from the LDP presidential election in 2012, where he narrowly lost to his rival. At the time, Ishiba commanded strong support from rank-and-file members of the party. But in the end, the tepid backing he gained from his fellow LDP parliamentarians felled him.

This pattern of Ishiba tapping into support from the party’s rank-and-file, only to suffer defeat due to lackluster popularity with parliamentary members, more or less repeated itself when he once again ran for the leadership election in 2018 in a showdown with Abe.

Despite being a political foe of Abe, Ishiba was recruited to support the prime minister’s administration, first as LDP secretary-general and then as state minister in charge of regional revitalization. But in summer 2016, he broke free from Abe’s control by turning down Abe’s request that he stay in the Cabinet.

With that departure, Ishiba pivoted toward becoming the intraparty critic of Abe that he is today, a position with which few others in the LDP dare to align themselves.

Since then, he hasn’t balked at expressing criticism over cronyism scandals that roiled the Abe Cabinet, or the unconventional ways in which the prime minister sought to amend the pacifist Constitution.

This is not to say, however, that Ishiba, former defense minister and a self-acknowledged gunji otaku (military geek) with extensive knowledge of security issues, is opposed to the idea of constitutional revision.

In fact, his proposed overhaul of the war-renouncing Article 9 — a clause that has long constituted the crux of Japan’s postwar identity as a strict pacifist nation — is more radical than that pitched by Abe.

While the pragmatic Abe has sought to minimize changes to the politically sensitive clause, Ishiba has called for a much stronger military presence, standing by the position that the LDP shouldn’t abandon a constitutional revision plan it adopted as a party in 2012.

Both the LDP’s 2012 constitutional amendment plan and Ishiba’s own proposed update of Article 9, unveiled in 2018, involved the bold step of deleting phrases about Japan’s disavowal of “war potential” and the “right to belligerence.”

Partly because of his unique standing as an Abe critic, media surveys have frequently shown Ishiba emerging as the top public favorite to replace Abe as the prime minister.

He is also media-savvy, actively blogging, updating his YouTube channel — Ishiba Channel — and even once sending social media into a frenzy of glee with his cosplayed appearance as Majin Boo, a baby-like antagonist in the popular anime series “Dragon Ball,” at an event held in Tottori Prefecture, home to his constituency.

His professed love for Candies, an all-female idol trio from the 1970s, and geeky hobbies such as train-spotting, have also made him a sufficiently relatable figure for the public to take a shine to him.

But the kind of popularity he enjoys with the public has eluded him within his own party.

Ishiba currently heads a 19-member LDP faction called Suigetsukai, but it is the second-smallest group of all, and he is largely shunned by party heavyweights such as Abe and Finance Minister Taro Aso.

Japantimes / Balkantimes.press

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.