Recognizing our confirmation biases

Confirmation bias is the tendency to process information by looking for, or interpreting, information that is consistent with one’s existing beliefs. This biased approach to decision-making is largely unintentional and often results in ignoring some information. Existing beliefs can include one’s expectations in a given situation and predictions about a particular outcome. People are especially likely to process information to support their own beliefs when the issue is highly important or self-relevant.

This can happen from early years for some people and impact our ability to gain qualifications and change our life course. It may have nothing to do with talent and ability.

When we see a young person in school or the community and they are having challenges with learning impacting their behavior, we can draw conclusions that may come from a limited set of information. How we view the young person may also be influenced by training and experiences that we have had.

Time pressures and a lack of knowledge have been cited by teachers as factors that negatively influence the ability to support pupils for example with ADHD (1).In one study where referrals of ‘Children in care and adopted children were referred to a specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) team, they found under-diagnosis of common Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs) and mental health conditions but over-diagnosis of attachment disorder (2).

The lens we look through influences what we see.

Assumptions can be made, such as noted in this study, that because the children had been ‘in care’ their challenges were all related to attachment. Neurodevelopmental Disorders had been overlooked altogether.

Neurodiversity- the rationale for taking a person-centered approach

Checking out our assumptions

Having the ability and opportunity to gather information allows us to consider the different potential conclusions but it does require us to stand back and have a really good look at the information objectively and pull the pieces together.

Wrong or missed recognition = can mean less/no support and we end up devaluing that person’s potential too. (We know children who are excluded get fewer GCSEs and have lower chances of gaining employment and greater risk of entering the justice system).

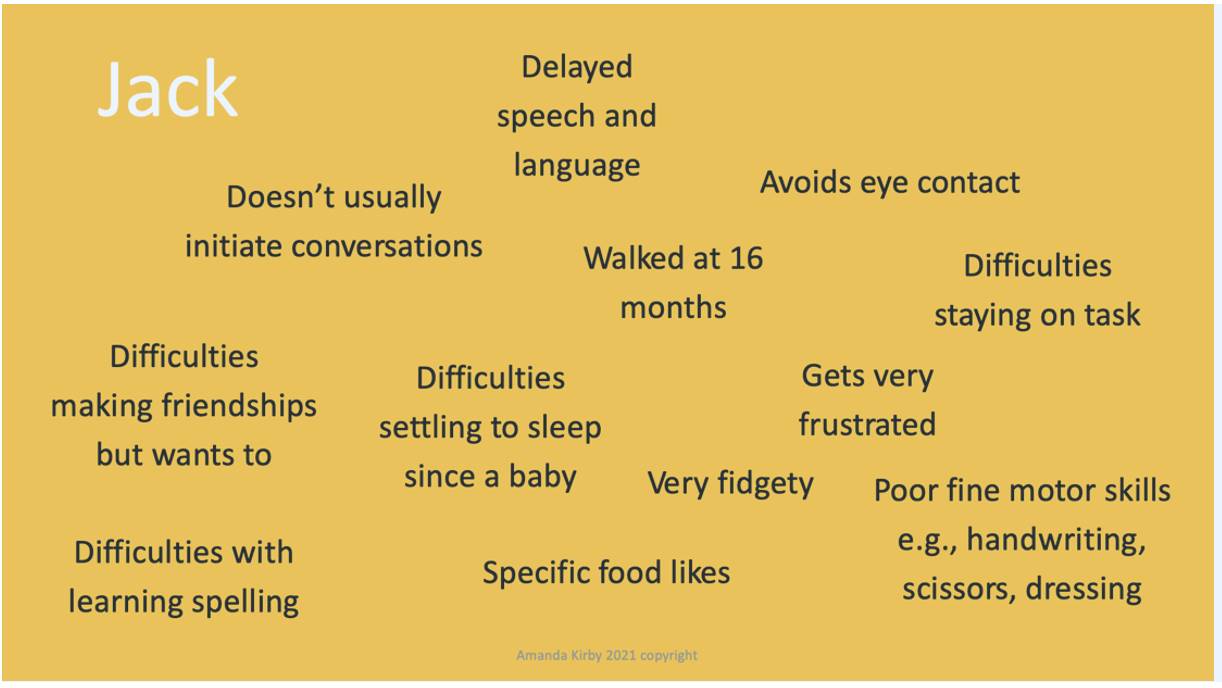

Let’s start by looking at Jacob (who is also called Jack) born in January 2007.

If you want to, read the following box and write some notes about your initial thoughts about Jack and his challenges.

**At this point, you only have this information.**

What did you think?

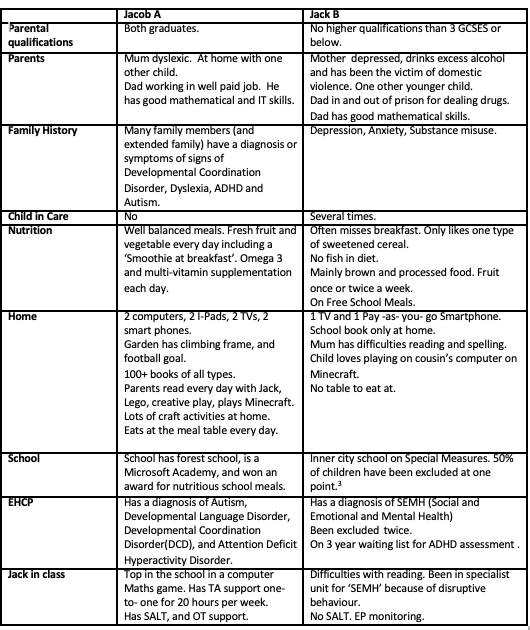

In reality, there are two Jack’s born on the same day but in two very different places by two sets of very different parents in the UK. Jacob is from a market town in Middle England and Jack from the North East or he could be from a town in the Welsh Valleys. When you start comparing the two boys you start to see the same presenting challenges in school but potentially very different interpretations. Additionally, there are huge differences in their lives.

Jacob and Jack live very different lives there is no doubt. However, their challenges presented in school are the same but the interpretation has been different resulting in different outcomes. Their lives differ in so many ways that can impact their learning outcomes. This includes the daily patterns and habits such as the opportunity to read and be read to and have a conversation. Jacob has a table to sit at and nutritious food to eat, outdoor space to play and computer access to play and learn. The other has none of these.

Jack’s Mum has had to survive on very little money, with her partner in and out of prison. There is an example of intergenerational impact. She left school at 16 years with no qualifications and low literacy skills. She is concerned for Jack but doesn’t know how to access help or what there is. She has no internet access apart from her phone and low digital skills. She is not surprisingly, depressed. Jack has gone into foster care for periods of time in the last couple of years.

Jack’s father is one of the one in three in prison(7) who has also undiagnosed ADHD and long-term dependency on a variety of illegal substances. His impulsive behaviour and addictive nature have got him into trouble. If you met him you would say he was bright and articulate but gets frustrated. Under the influence of drugs, he has hit Jack’s mother a number of times.

In school, Jack gets frustrated in class as he doesn’t always understand what is being asked of him. This results in him being disruptive and he has been excluded from school several times. His social skills are poor and his speech is not always clear. His reading and writing are falling further behind during this last year. He has few friends and intermittent schooling has made him even more isolated.

Jacob’s life is very different.

He has educated parents whose nursery alerted them to Jacob’s speech and language delay. They sought information and were able to navigate the system and gained an early and comprehensive diagnosis for Jacob. They have got professional help for him. He has an Educational Health Care Plan.

He is at a primary school with a forest school and impressive computer access. He has time allocated with a teaching assistant who helps him navigate times of change in class and keeps him on task and reinforcing positive social interactions that he has difficulty with. Without this help, Jacob could be disruptive to others in the class. During Covid-19 he has gone to school for some of the sessions and using the computer. He became top in his school for an online maths game. His school teachers can see he has real talents in mathematics and even learning to code.

Neurodiversity is all about our brains.. we are what we eat!

Different balls in the bucket?

If we use an analogy of balls in the bucket which represent different strengths and challenges in the young person’s life we sometimes only view balls of a certain colour. We give a diagnosis only when a threshold is reached. However, Jack and Jacob have some balls of a similar color but how we view and respond to these is very different.

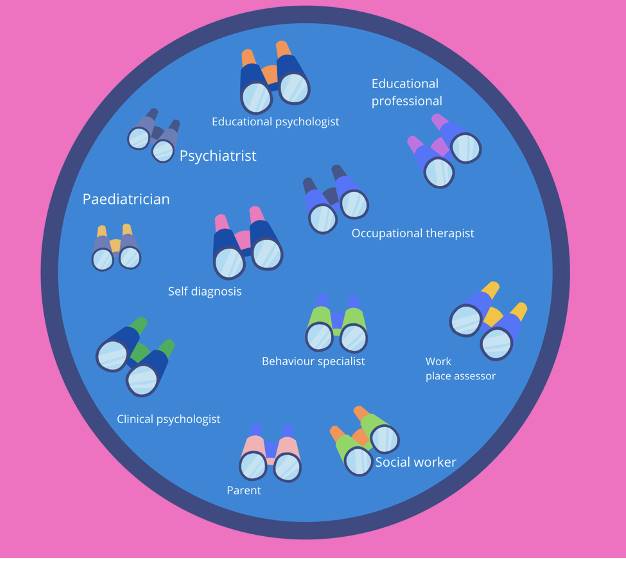

Creating a young person’s profile

Each child will have an individual profile of needs and abilities. There will be different local and social factors that result in different pathways to diagnosis (or not). Intersecting and compounding forms of discrimination and disadvantage create these different outcomes.

Remember Jack and Jacob have the same profile of challenges but the ‘wrap around’ in their lives is significantly different. One child has an EHCP for neurodevelopmental conditions and the other a label of SEMH. We can see poverty at play in Jack’s life. Middlesbrough for example has four times the level of Free School Meals compared to many schools in Buckinghamshire(6).

Socio-economic status is linked to longer-term outcomes and increasing impact as children progress. It also relates to parental resources, the locality of the school and quality of teaching and a disconnect between home and school(8). Whether you come from Jacobs home town or Jack’s parents often have to fight for what they need for their children. This requires good literacy levels and being articulate. It often takes money to do so too.

Goldilocks, diagnosing and Neurodiversity- getting it ‘just right’

What is SEMH?

Social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs has been defined as a type of special educational needs in which children/young people have severe challenges in managing their emotions and behaviour. They often show inappropriate responses and feelings to situations.

Some characteristics of children with SEMH may include:-

· Disruptive, antisocial and uncooperative behaviour

· Temper tantrums

· Frustration, anger and verbal and physical threats/aggression

· Withdrawn and depressed attitudes

· Anxiety and self-harm

· Stealing

· Truancy

· Substance misuse

Have Jack’s challenges been viewed as ‘behaviours’ and assumed to be more associated with the external factors than potentially related to neurodiversity as well?

Children born in Middlesbrough are more likely to be absent from school than national and regional averages and more likely to be excluded from school. Forty per cent of children who are in local authority care have Special Educational Needs (SEN), 20% have an Education, Health and Care Plan. If we miss vital information we can end up drawing the wrong conclusions.

Interestingly, when we look at data from children who have an Education, Health Care Plan and compare those in care from the mainstream population we can see significant differences in their diagnosis (4,5).

Why are things so different for Jack and Jacob?

Why should it be that Jack is more likely to get a diagnosis of SEMH rather than Autism or Speech, Language and communication challenges? There is good evidence of higher rates of neurodiversity among children excluded from school like Jack but usually no routine screening for these traits.

In one study of excluded children, the rate of ASD was 20 x the national average (9). In the large- scale longitudinal study in the Avon ALSPAC cohort of those excluded by age 8 years, 19% had ADHD and 23% had language development in the bottom 10% (10). In an older study, a sample of pupils who had been permanently excluded pupils from thirty-three Sheffield secondary schools found that 76% were ≥2 years behind their peers in reading (11).

Despite extensive evidence of co-occurrence between conditions and this also interlinked with adversity we often still seek single diagnoses for children who have intersecting challenges (12).

Neurodiversity – needs to be inclusive and not exclusive

By embracing the concept of neurodiversity ( that we all differ in how we think, move, act and process information) and recognising the extensive (see last weeks newsletter) evidence of co-occurrence, it allows us to move from a narrow diagnostic approach to a whole-child/person and needs approach.

We can create a formulation from information gathered from multiple sources and support children and adults functionally. This allows each child to potentially have an equal opportunity to gain support earlier and reduce biases. If we continue to have a model that only intervenes with a narrowly framed diagnosis, Jack will inevitably become an unemployed Dad and the intergenerational cycle will continue.

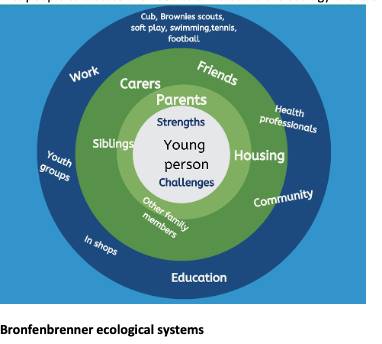

A whole-person approach is a systemic approach

This considers the child in the context of their lives and the society they live in but is not judgemental. Bronfenbrenner (13), was one of the first people to discuss the need to understand the ecology of the child.

Bronfenbrenner ecological systems

Inclusion means accessing and being able to use the technology

Jack’s mum doesn’t have access to the internet apart from her pay-as-you-go phone and if she did she wouldn’t know where to ask for information or be able to read or complete forms she would need to fill in ( I checked one site for a local authority and the website had no accessibility tools and needed a reading age of someone in Year 12 to understand and read the content!)

Jacob, despite being at a great school and getting support. Don’t think this is easy for him or his parents. Without help, he could have no friends and his behavior could easily spiral. He too could also be a statistic potentially ending up in the alternative provision. So often children developed secondary challenges as a consequence of the delay or misdiagnosis. They have lowered self-esteem, and a negative concept of themselves and believe they must be a failure. We need to see ‘behavior’ as a means of communication and never a diagnosis.

Saves money too!

Increasing the ability for early comprehensive identification can also reduce the flow downstream and for some stop the route into the justice system. The economic impact on society is great. Inclusion is all about equity and reducing the disparities in society to allow both Jack and Jacob to have a chance at a bright future.

I was talking to one very articulate Mum of a child with a diagnosis of Autism this week. She has no school for her child to go to, and legal battles that she mentioned could add up to an extension on her house. Her child remains at home with no school to go to. This is a tragedy.

As a parent of neurodivergent children, I felt alone at times trying to work out what were the processes are and how to best navigate them for my bright and capable children. All I wanted was their talents were optimized and they could be their best. I think that’s what most parents want for their children.

Neurodiversity should not be about where you live. Autism should not be seen as a trump card or lottery win and mean more to society than ADHD or SEMH.

Neurodiversity is not an exclusive club- it is us all.

Building a picture – 6 Ps

- Preparation – Awareness about neurodiversity and mental health and wellbeing.

- Precipitating challenges- the understanding of tipping points.

- Perspectives i.e., context e.g., home, school, family life, working life of parents.

- Predisposition to increased risk of ‘fall out’ from past and present events e.g., ACEs, illness, loss, LACYP, trauma, and head injury.

- Protective factors e.g., scaffolds in place, parental support, intervention, improved nutrition, housing.

- Positive factors e.g., strengths, resilience, self-esteem, peers.

Professor Amanda Kirby is a passionate campaigner about neurodiversity and the impact of supporting all in society to maximize talents. She is the CEO of Do-IT Solutions. This is a tech-for-good company. Do-IT has developed neurodiversity screening systems that are person-centered, age and context-related. They work successfully in schools, colleges, apprenticeships, prisons, and in different employment settings. Do-IT delivers training and consultancy to help organizations make the cultural and practical changes to be truly inclusive.

References:

1.Woolgar M & Baldock E (2015). Attachment disorder versus more common problems in looked after and adopted children: Comparing community and expert assessments. Child & Adolescent Mental Health. 20(1), 34-40.

2. Richardson, M. Moore, D. Gwernan-Jones, R. Thompson-Coon, J. Ukoumumme, O. Rogers, M. Whear. R. Newlove-Delgado T. Logan, S. Morris, C. Taylor, E. Cooper, P. Stein, K. Garside, R & Ford, T. (2015). Non-Pharmacological Interventions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) delivered in school settings: systematic reviews of quantitative and qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment. 19 (45) 1-470.

3. https://www.gazettelive.co.uk/news/teesside-news/children-deserve-better-dozens-school-19261462 ( Accessed March 2nd, 2021)

4. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/characteristics-of-children-in-need/2020 ( Accessed March 2nd , 2021)

5. Children Looked After in England (2019) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/850306/Children_looked_after_in_England_2019_Text.pdf

6. https://lginform.local.gov.uk/reports/lgastandard?mod-metric=2174&mod-period=1&mod-area=E10000002&mod-group=AllGeographicalNeighbours&mod-type=comparisonGroupType ( Accessed March 2nd , 2021)

7. Young, S., Gudjonsson, G., Chitsabesan, P. et al. Identification and treatment of offenders with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the prison population: a practical approach based upon expert consensus. BMC Psychiatry 18, 281 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1858-9.

8. Socioeconomic Disadvantage, School Attendance, and Early Cognitive Development: The Differential Effects of School Exposure. Ready, Douglas D. Sociology of Education, 2010, Vol.83(4), p.271-286

9. Barnard, J., Prior, A. & Potter, D. (2000)Inclusion and autism: is it working?

10. Paget, A. et al.(2018) Which children and young people are excluded from school?

Findings from a large British birth cohort study, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Child. Care. Health Dev. 44, 285–296 (2018).

11. Galloway, D., Martin, R. & Wilcox, B. Persistent Absence from School and Exclusion from School: the predictive power of school and community variables. Br. Educ. Res. J. 11, 51–61 (1985).

12.Cleaton MAM, Kirby A (2018) Why Do We Find it so Hard to Calculate the Burden of Neurodevelopmental Disorders? J Child Dev Disord. 4:10.

13. Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.