THE SAHEL

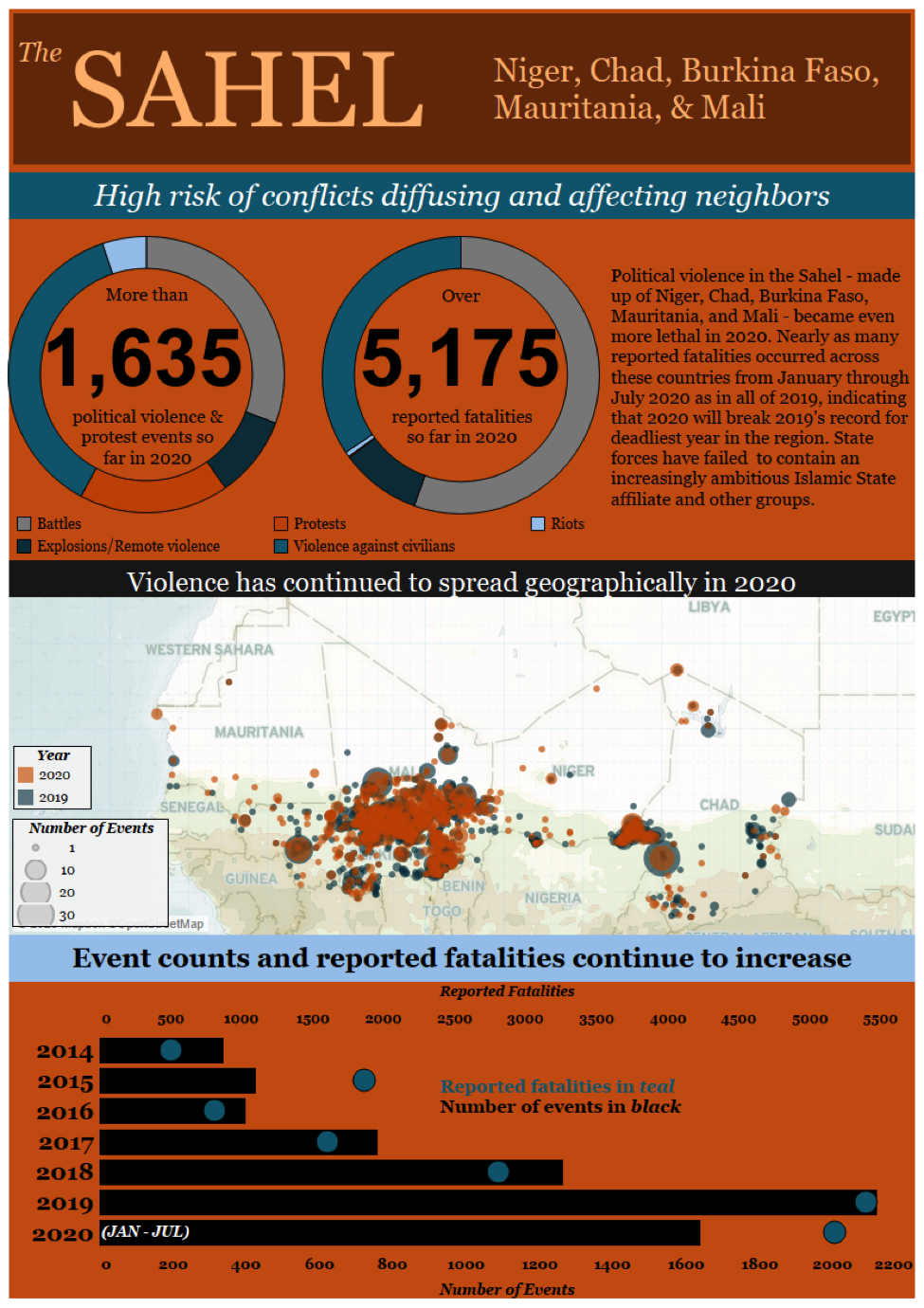

In the Sahel, persistent conflicts have raged on for more than eight years and show no signs of abating. Instead, the multidimensional crisis is escalating and expanding across the region. Halfway through 2020, the number of reported fatalities in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger has either neared or surpassed the full total for each country in 2019.

The rising death toll is driven by multi-directional violence perpetrated by primarily jihadi militant groups, state forces, and ethnic/community-based militias (Sahelblog, 24 July 2020).

In the first months of 2020, the region experienced a sharp rise in violence targeting civilians by government forces, as local and foreign forces stepped up their operations to counter the jihadi onslaught by the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’ah Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS), or the Greater Sahara faction of Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) (for more, see ACLED’s report on state atrocities in the Sahel).

At the beginning of 2020, ACLED assessed a high risk of conflicts in the Sahel diffusing and spilling over into neighboring countries amid a continuous southward encroachment of mobile threats to the security of West African coastal states (ACLED, 23 January 2020).

This came to pass in June, when Ivory Coast suffered a deadly attack on a border post in the country’s extreme north. Militants believed to be JNIM staged an assault on a mixed army and gendarmerie position in the village of Kafolo, killing 14 troops (Koaci, 2 July 2020).

The attack in Kafolo represented the first jihadi militant attack in Ivory Coast since the 2016 shootings at the Grand-Bassam resort.

Fighting between militant groups is also intensifying. After ISGS was formally integrated into ISWAP, tensions and skirmishes increased with JNIM. Ideological divisions have hardened between the two groups, and ISGS has increasingly challenged the hegemony of its Al Qaeda counterpart as its ambitions have grown (CTC, 31 July 2020).

The rising tensions escalated into open warfare in Mali and Burkina Faso in early 2020, and evolved into a full-fledged turf war throughout the first half of 2020. In the first six months of 2020, ACLED records 34 armed engagements between the two jihadi franchises, leaving more than 300 militants dead. Considering the upsurge in jihadi-on-jihadi fighting, militant groups are currently, to a significant degree, contesting territory more between each other than with the concerned states.

In Burkina Faso, the parliament approved a bill authorizing the training and arming of civilians to supplement conventional forces in their fight against jihadi militant groups (Le Faso, 21 January 2020). First and foremost, the creation of volunteer fighters, or Volunteers for Defense of Homeland (VDP), represented a formalization of pre-existing community-led security and largely ethnic-based militias — including Koglweogo and Dozos — within state structures, contributing to further escalation of violence.

Moreover, the recent killing of the mayor of Pensa and a complex ambush against the security escort of the president of the Higher Council for Communication highlight the growing conflict in Burkina Faso, and the imminent risks posed ahead of presidential and legislative elections planned for November.

In neighboring Mali, JNIM militants and Fulani militias have conducted incessant attacks against Dogon villages to isolate and subjugate Dogon communities, as well as to hamper the harvest season. These attacks have led many Dogon villages to distance themselves from the majority-Dogon Dana Ambassagou movement. In this context, JNIM posited itself as an arbitrator to solve the conflict between Fulani and Dogon in Koro, in the central Mopti Region, thus increasingly taking on governing responsibilities.

Beyond armed conflict, Mali is currently experiencing a socio-political crisis amid a series of mass demonstrations against the regime, to which government forces have responded with brute force.

The demonstrations — monikered the Movement of June 5 – Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP) — are organized by a loose coalition of religious leaders, opposition figures, and civil society, spearheaded by the influential imam Mahmoud Dicko, who has called for civil disobedience until president Ibrahim Boubacar Keita resigns. Keita is viewed by the protest camp as the embodiment of bad governance, corruption, and the state’s failure to reduce conflict (ECFR, 22 July 2020).

In Chad, militants of Jama’atu Ahlis-Sunna lid-Dawati wal-Jihad (JAS), or Boko Haram, carried out the deadliest attack ever recorded in Bohoma, killing at least 92 soldiers (Jeune Afrique, 25 March 2020).

Chadian authorities responded to the attack by launching the 10-day operation “Anger of Bohoma,” and claimed to have killed 1,000 insurgents as a result of the operation (Alwihda, 9 April 2020). While the army triumphantly said it had chased away Boko Haram from the lakeside, militant activities soon resurged. President Idriss Deby admitted in an August interview that Boko Haram militants “would continue to wreak havoc in the Lake Chad region” in spite of the large-scale offensive (France24, 9 August 2020).

The creeping progression of militant groups constitutes an immediate threat to the northernmost border regions of countries such as Benin, Togo, and Ivory Coast. Increased jihadi militant activities have also been recorded in recent months in Mali’s southern regions of Sikasso, Kayes, and Koulikoro.

There is an imminent risk that hostilities between JNIM and ISGS will spread to areas so far spared from violence, and potentially exacerbate conflict along ethnic or tribal fault lines. Increased competition between the groups could lead to deadlier attacks.

Meanwhile, the impact of the coronavirus pandemic has so far been relatively limited in Sahelian countries. Measures to counter the spread of the virus were difficult to impose by the authorities and triggered popular discontent due to their impact on mobility and economic and daily life.

For instance, in Niger, the closure of mosques and ban on Friday prayers resulted in violent demonstrations in several localities. To reduce tensions, the Nigerien government authorized the reopening of mosques. In Burkina Faso, tensions arose from the closure of markets; the measure was lifted after five weeks.

A curfew declared by the Malian government was met by demonstrations and the curfew was then lifted after six weeks. Thus, authorities often quickly submitted to popular demand in order to reduce tensions arising from the potential economic impact of pandemic related measures.

If you want to read the articles in order, click on PREVIOUS or NEXT PAGE

Or, Please click through the drop-down menu below to jump to specific cases.

MEXICO

YEMEN

INDIA

SOMALIA

IRAN

AFGHANISTAN

ETHIOPIA

LEBANON

UNITED STATES

ACLED / Balkantimes.press