Paul James holds out his woolly red hat and the man in the suit drops three coins into its depths before disappearing inside Embankment Station

A boy in a vampire costume hurries past and pulls a mock-scary face at the first Welshman to play at a World Cup since 1958. Another man shoots off to buy him a coffee from the nearby Starbucks.

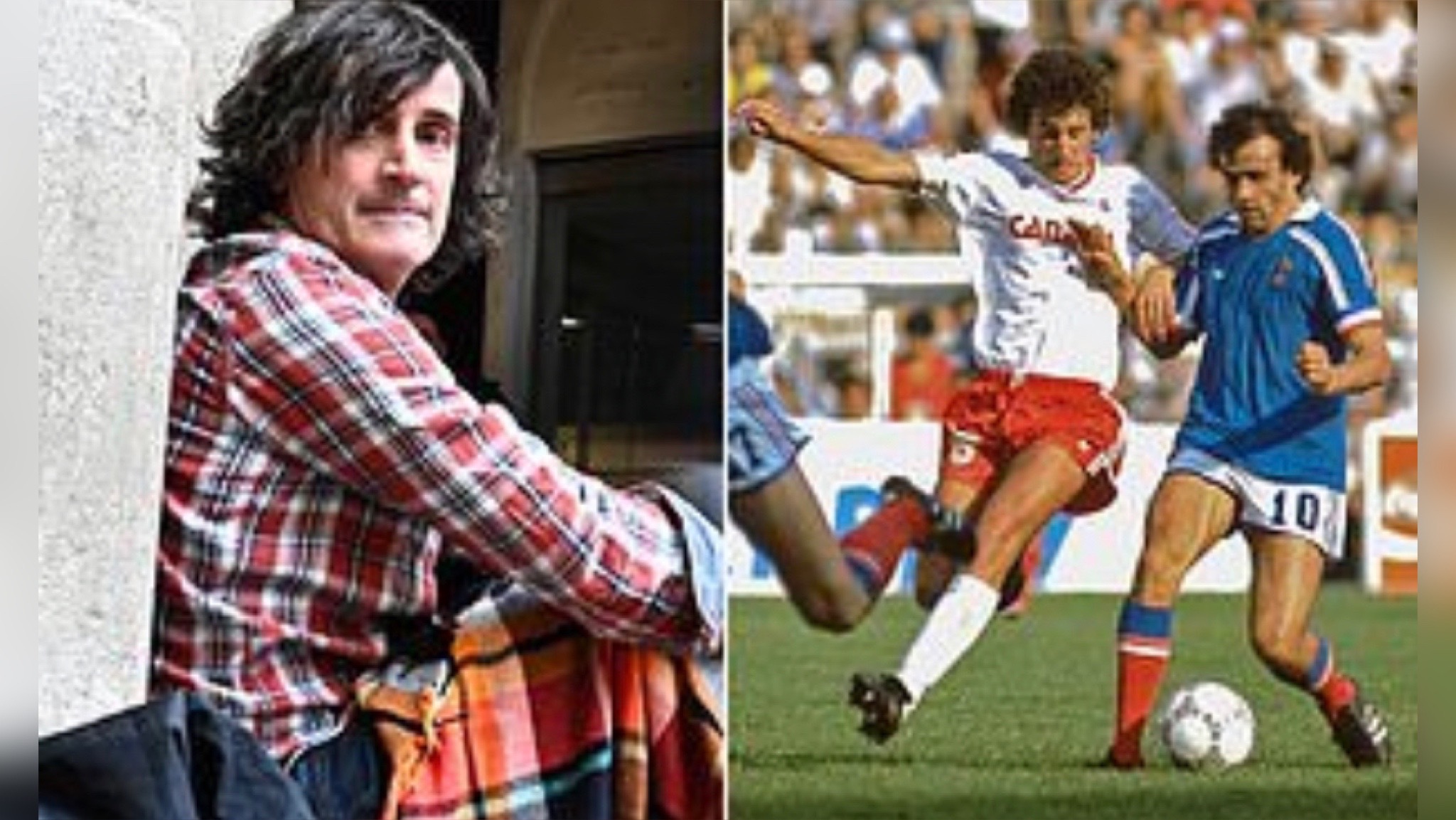

Paul James played at a World Cup, is an Olympian, and went to the same school as Gareth Bale. Now, he's on the streets of London.

I've spent a lot of time with him over the past few months. This is his story.https://t.co/RzDGt5Yfai pic.twitter.com/LXLAxFvSQr

— James Sharpe (@TheSharpeEnd) December 31, 2022

Many others catch the eye of the man smiling at them from under the chequered blanket only to snap their heads back and march on.

Many more hurry past without as much as a glance towards the man who shared an international pitch with Glenn Hoddle and Gary Lineker and marked France’s Michel Platini in Mexico in 1986.

James is one of Wales’s – and Canada’s – most decorated footballers. He was born in Cardiff and grew up on his parents’ farm before the family moved to Toronto in 1980.

Six years later he started all three of Canada’s group games at their only World Cup before Qatar. In 1984, he lost on penalties to Brazil in the quarter-finals at the Olympics.

He played 47 times for his country. As a coach, he helped Canada women’s U20s to a CONCACAF title and led their male counterparts to the World Cup

His face hangs on the ‘wall of fame’ at Whitchurch High School, the Cardiff state school famed for churning out international athletes, alongside the likes of Tour de France winner Geraint Thomas, former Lions captain Sam Warburton and Wales captain Gareth Bale.

And while Bale led Wales into their first World Cup since 1958 and Canada embarked on their first since 1986, James is on the streets of London.

He’s been unemployed for the last 13 years and without a permanent home for six. He returned to the UK from Canada just before the pandemic, angry at his treatment across the pond. James believes, with fury and unshakeable resolve, that he faced discrimination in Canada for his historic use of crack cocaine.

Until a few months ago, when he found shelter at a hostel near Holborn, in a room recently also occupied by two mice, he slept on scraps of cardboard at Charing Cross or Westminster Cathedral. Before that, he was on the bitter streets in Toronto.

We meet outside Embankment, one of the places around the capital where James often sits and awaits the kindness of others. Sometimes there, sometimes at Piccadilly or the Strand. He doesn’t call it begging – he calls it fundraising.

‘If you want to know what the look of utter contempt and disgust looks like, do this,’ James tells The Mail on Sunday. ‘But if you want to see moments of amazing kindness and humanity, do this as well.’

What is it he raises funds for? ‘To be independent,’ he says. ‘To regain a semblance of normality. To able to wear my own clothes and shoes and not second-hand ones. To not have to fundraise to purchase my own items.

‘To regain independence from the metaphorical prison condemned as an innocent for thirteen lost years, not by the UK to whom I feel indebted, but Canada as a nation. To find and rekindle the passion, enthusiasm, and positivity I once had. And, on top of everything, to find an avenue to connect with people.’

James often gives his email address to those who stop to talk, asks them to Google his name. Few, he says, ever email him. He hopes this might change that.

He watched the World Cup on the television in his hostel room. He sat on the edge of his bed on the fifth floor as Harry Kane lined up his first penalty against France.

When Olivier Giroud made it 2-1 to France, he left the hostel and walked through the empty streets towards the sounds from the local pubs. He heard cheers ring against the night sky as England won their second penalty. He stepped inside to the screams of despair as Kane missed it.

‘England were better on the day,’ says James. ‘Kane missing the second penalty was not where the game was lost. It was in the two goals conceded.

‘Failure to pressure the ball on the first and a failure to stop the quality of the cross on the second in tandem with England’s centre-backs watching the ball losing Giroud. Both were unavoidable errors.’

James is a passionate speaker, with a magnetic, manic quality about him. One moment he quotes Shakespeare or Jordan Peterson or Bruce Lee or Steven Bartlett off Dragons Den.

The next, he leaps off the bench to reenact the paranoid terror that follows smoking crack cocaine or scurries back and forth to demonstrate how Bale’s lack of pressing held Wales back at the World Cup.

‘Wales showed the fighting spirit I am so proud of. Realistically, though, they were out of their depth.’

He’d hoped England and Wales would wear the One Love armbands in protest to the treatment of the LGBT community in Qatar. ‘Through sport you can achieve social change, but you must f*****g demand it, right?’

James, a former team-mate of Justin Fashanu, felt disgust at the FIFA president Gianni Infantino’s ‘bigoted, obscene’ speech before the tournament in which he declared ‘Today, I feel disabled. Today, I feel gay.’ Infantino, says James, appeared ‘more Machiavelli than Cicero’.

So, how did this happen. How did this Cardiff-born footballer, a decorated World Cup international, an Olympian, a successful coach a successful coach, a respected pundit, columnist and three-time inductee into the Canada Soccer hall of fame, with a BA from Wilfrid Laurier and a football MBA from the University of Liverpool end up on the streets of London?

For James, a simple strand runs through his remarkable life: the stigma endured for using crack cocaine.

He smoked cocaine for the first time in 1998 and for the next decade developed, as James urges everyone to describe it, a substance use issue.

Not every day, sometimes weeks or months in between. ‘I couldn’t connect with anyone, to find an intimate partner in my life. Substance, and overwork, replaced that.’

James had a six-year relationship with Ashley Kelly who he describes as an ‘extraordinary person’. ‘I loved her to bits but could offer her nothing,’ he admits.

The stigma, he says, envelopes how society views drugs, even as far as the language.

‘I don’t think you should call anyone a drug addict, a crack addict, a junkie,’ says James. ‘The words conjure up irrationality and a series of labels which view those exposed as: criminal, scary, irrational, unreliable, to be avoided, diseased, loser, dirty, lazy, scum, non-employable. Can you see how disgusting that language is?

‘How do you ever recover from being labelled a homeless crack addict? You don’t.’

James is certain he lost his job as head football coach at York University in Toronto, where he led their men’s side to a national championship, due to discrimination against his drug use. When he offered to resign in 2009 as his mental condition and drug use worsened, he believes York had a duty of care to offer him support. He says York asked him to formalise his resignation. James claims he previously opened up to colleagues that he needed time away and went to rehab. He says he was forced to resign. York deny the accusations.

He tried to take York to the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal but was unsuccessful as he’d not complained within the year deadline. James argues his mental health and substance issues made that impossible.

He took his fight to the Canada Supreme Court in 2016 but, again, was unsuccessful. He’s since been on ‘at least a dozen’ hunger strikes in his pursuit of justice. He wants discrimination over drug use enshrined in law.

‘There’s never been a war on drugs,’ says James. ‘How can you have a war on inanimate things? There’s only ever been a war on people. And it is those most vulnerable who suffer most from the devastation of the stigma: social exclusion, marginalized, poverty.

‘If you arrive on the scene from wealth, power, Hollywood stardust or if you are endowed with political cache, you have the best chance of avoiding such a catastrophe.’

We sit in Victoria Embankment Gardens and James looks down at a picture from the World Cup in Mexico in 1986. There he is, in a white Canada shirt, red shorts and white socks, sticking out his leg to sweep the ball away from the smaller opponent trying to shield it from him: France’s No.10, Michel Platini.

Canada lost all their group games but gave a good account of themselves. This year in Qatar was their first World Cup since.

‘What we achieved at that World Cup was phenomenal, when I think of how good we weren’t,’ he says. ‘We performed miracles to keep the score lines so predictable.’

In the build-up to the tournament, James started in Canada’s warm-up game against England in British Colombia. Hoddle and Lineker both featured for Bobby Robson’s men with Mark Hateley scoring the only goal in a 1-0 win.

James scored against Costa Rica on Canada’s way to winning the CONCACAF Championship and securing qualification for Mexico.

He fractured his toe a few months before but played on with an oversized boot to allow for the extra padding, so big it flew off during games.

After the France defeat in Mexico, he swapped shirts with defender Maxime Bossis. He hopes his sister still has it.

He’s not seen her or his family in four years. His mother passed away in June but James only found out two months later. He hopes this interview might help him reconnect with his father.

James’s national team playing days ended after he was embroiled in a bribery scandal during a tournament in Singapore, just months after the World Cup. Four Canada players accepted cash to influence results of games.

Ahead of the semi-final, they asked James to join them. He agreed and was given $10,000. He later returned the cash and testified against the four in court.

Asked how it feels looking at the pictures of him and Platini after all these years, he replies: ‘It’s mixed. The pride in knowing you were part of something special but then, in your later life to be deliberately treated with such distain and disgrace for a profoundly human condition, it’s unacceptable.’

James has reached out to former team-mates and colleagues since moving back to the UK. On our first meeting, James says the jeans he wears were donated by Chris Ramsey, the QPR technical director who was England’s under-20s coach at the time James led their Canadian counterparts.

One shivering night sleeping in Victoria, his former team-mate Paul Peschisolido, husband of West Ham vice-chair Karen Brady, took him a blanket and some food. Peschisolido recently brought him some new trainers and a coat for James’s 59th birthday

James has picked up bits of work, like sweeping the roads on Oxford Street before a knee injury made it impossible to continue.

It has taken a long time for James to agree to the interview. We meet four times over the past few months, for a few hours at a time, and exchange numerous emails that he often sends from a public library near King’s Cross.

At various points he pulls his consent. He doesn’t know if he can open himself up to anymore ridicule but, in the end, he believes it can help, not just him but others.

After his hours of fundraising, James will walk back to the hostel. He donates a portion of his collection to the other homeless people he passes on the way. For this interview, his only request was that The Mail on Sunday make a donation to London homeless charities.

James does not want you to feel sorry for him. He’d rather you feel angry. But, more than anything, he hopes it makes you think, makes you consider how society treats its most vulnerable and how a decorated World Cup footballer ended up here.

‘My football career was everything,’ he says. ‘I should not have lost a day’s work. If I was to end my life tomorrow, which I won’t, people would understand. Because it’s been a f*****g brutality.’

All this is only part of the story. Our conversations, he says, barely scratch the surface. There’s hundreds of emails he’s sent to the likes of Infantino and Justin Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada.

There’s the tons of legal documents, some 200-pages long, sent to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario and to Canada’s Supreme Court. There’s the website he started called ‘Confronting the Stigma of Drug Addiction’. There’s his 2012 ebook memoir entitled Cracked Open.

Only then, he says, will anyone truly understand the depths of the discrimination and the anger. Only then, will they understand why he’ll never stop fighting.

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.