A federal judge in Virginia approved the expedition Monday, calling it “a unique opportunity to recover an artifact that will contribute to the legacy left by the indelible loss of the Titanic.”

Because of a backlog of personal messages, the wireless operators had ignored ice warnings from other ships. Banal good wishes soon gave way to increasingly desperate calls for help. Operator Jack Phillips died after refusing to leave his flooded post.

“He was a brave man,” his fellow wireless operator told the New York Times a few days later. “I will never live to forget the work of Phillips for the last awful 15 minutes.”

The company R.M.S. Titanic (RMST) still must get a funding plan approved by the court, a prospect made more complicated by the coronavirus pandemic. It plans to launch the expedition this summer, using underwater robots to carefully detach the Marconi and its components from the ship.

“If recovered, it is conceivable that it could be restored to operable condition,” RMST said in one filing. “Titanic’s radio — Titanic’s voice — could once again be heard, now and forever.”

The recovery project has been vociferously opposed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, whose representatives argued in court that the Titanic, sunk about 370 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, should be respected as a grave rather than mined as a museum supply.

At its heart, the years-long legal dispute is an emotional one. Who can claim the Titanic? Should the public have the right to see as many of its treasures as possible, from the comfort of a Las Vegas casino or a Florida interactive museum? Or should the remains of the victims be left in peace, their effects seen only by scientists underwater?

“Titanic has always been a singular case of passionate, strongly held opinions,” said maritime archaeologist James Delgado, who helped map the ship on a 2010 expedition. “For some it’s a memorial, for some it’s a historic site, for some it’s where a family member died. For others it’s an ultimate tourist destination, and for others it’s a business opportunity. How you balance all of that is very difficult.”

Because of the intricacies of maritime law, the federal court in Norfolk has been tasked with striking that balance. But the Titanic is also a fulcrum for a broader battle over who controls the seas — companies and courts, or governments.

It’s a fight that has gotten heated, and personal. RMST’s attorneys once compared a British archaeological group to the Taliban. One marine archaeologist working for the company, John Broadwater, quit the project just days before the ruling. Emails show former colleagues at NOAA refused to talk to him about the Titanic once he joined.

“I think it would make a wonderful exhibit, but it’s definitely a complicated situation,” Broadwater said in an interview.

The government position is that the Titanic site should be protected and preserved where it is, while the Marconi is “standard off-the-shelf” equipment of the time that has little value outside the ship.

“Just like a lion is much better appreciated in the wilds of the African savannahs than it is stuffed in a museum, so too does the Marconi apparatus best tell its story and share its value where it is,” the National Park Service’s Submerged Resources Center chief wrote to the court.

The company responds that NOAA is hardly in a position to act as gatekeeper, having approved an expedition group last year that accidentally jostled the ship’s rail. It pledges to use underwater robots to carefully extract the Marconi, only if deemed safe.

“RMST is left to wonder why has NOAA gone to such great lengths to raise scores of questions about the competency, plans and equipment of a team that has actually led or participated in numerous successful expeditions to the Titanic, and the recovery of thousands of artifacts from the ship since 1987, when it does not ask the same questions of other rookie expeditioners with no such track record,” the company wrote in a recent filing.

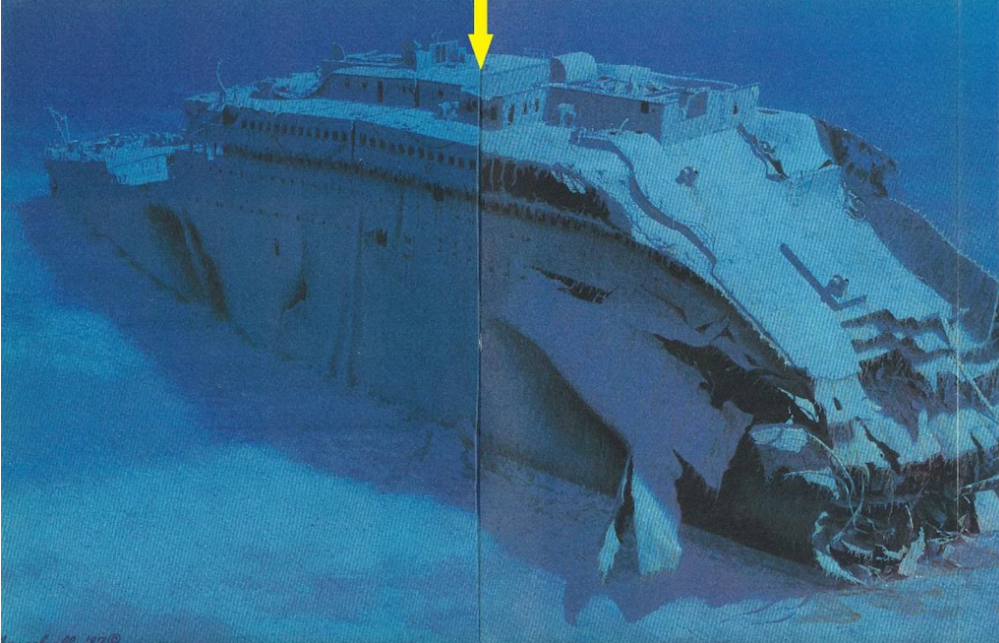

Moreover, it argued that the Titanic is rapidly deteriorating without any intervention; the ceiling of the room that holds the Marconi may well collapse soon.

“There are places where you can stick your finger through that rooftop,” oceanographer and RMST consultant David Gallo testified at one hearing.

Senior Judge Rebecca Beach Smith agreed, calling photographs of the deterioration “poignant.”

In the past thousand years, the basic principles of maritime law have not changed, and one is that whoever retrieves a wreck gets a reward. Where the wreckage is brought determines control.

It’s a rule meant to encourage clearing the sea of debris and restoring property to rightful owners. Historic wrecks that are expected to languish underwater forever are an awkward fit. But the same principles apply.

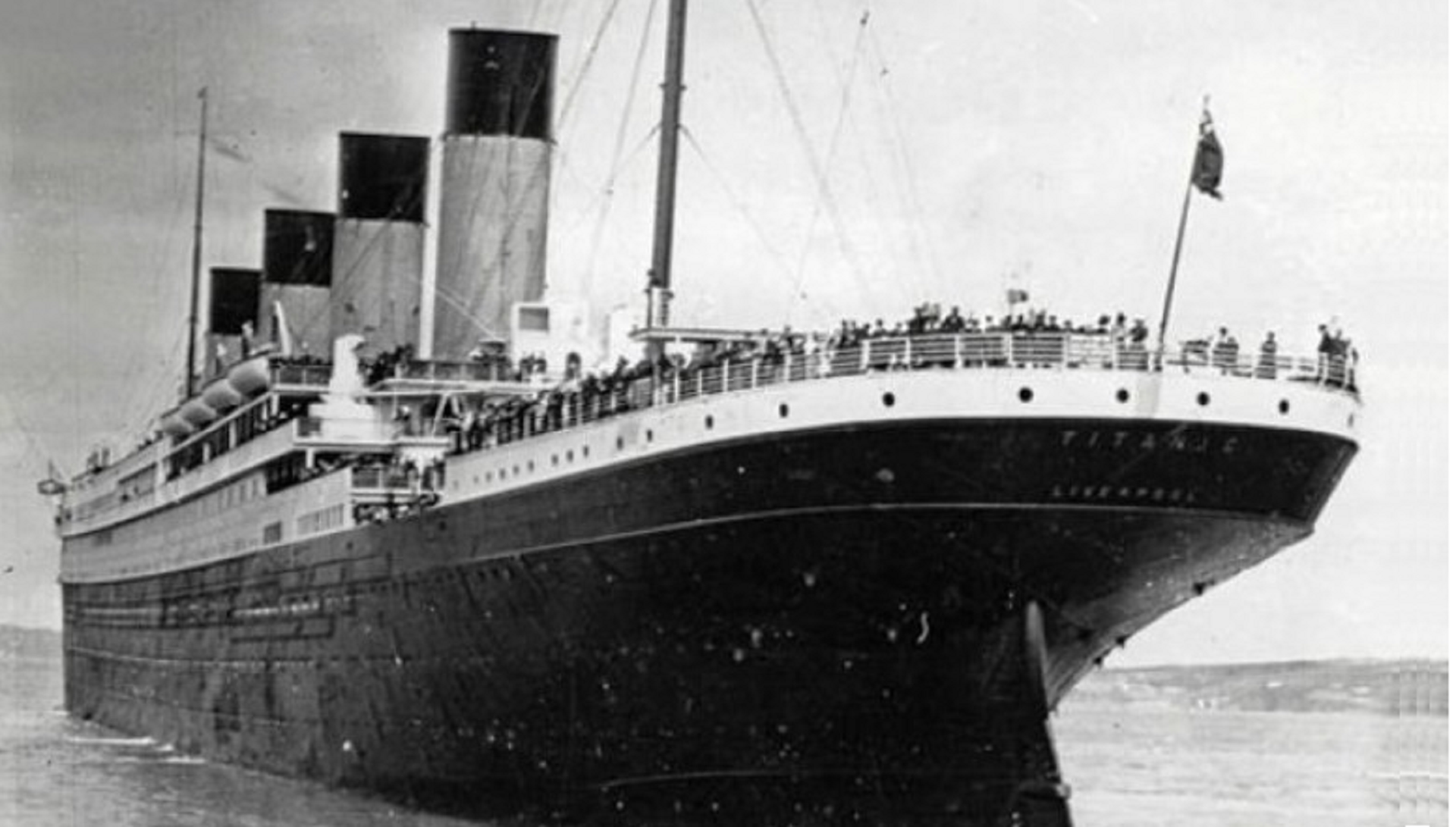

Within two years of the Titanic’s 1985 discovery by oceanographers, a Connecticut car salesman named George Tulloch had created RMST, made an expedition to the site and wrangled salvage rights by bringing a wine decanter into a Norfolk federal courtroom. The Virginia court became the arbiter of future exploration and recovery.

A salvor who declines to donate their winnings to the poor no longer risks “the curse and malediction of our mother the holy church,” as the law was written in the 1100s. But RMST is legally bound to act with public benefit in mind. The company cannot break up its collection of Titanic artifacts, and it needs permission from the court to touch or take anything off the ship. The only treasure the company can sell is coal (available online as an hourglass, snow globe or key ring).

RMST retrieved thousands of items from the field of debris around the ship — bronze whistles, leather luggage — and set up a touring exhibition. It advertised cruises to the wreck with Burt Reynolds and Buzz Aldrin.

Outside critics called it crass hucksterism; some at the company thought it was being too respectful. In a coup, when Tulloch was celebrating Thanksgiving in 1999, board members changed the locks on his office, according to news media reports at the time. The new leaders declared plans to scour the ship for $300 million in missing diamonds.

“We know there’s an awful lot of money under the water,” one shareholder told the Baltimore Sun.

Alarmed, the court brought in NOAA as a “friend of the court,” one that has viewed the company skeptically ever since.

“It is difficult to envision that, once out in the North Atlantic, contrary voices advocating caution (if any are allowed to be present) will be heeded or heard,” NOAA officials wrote recently.

The company was bought in bankruptcy in 2018. RMST lawyer David Concannon declined to comment Tuesday. In a February interview, well before the judge’s decision, he called the former owners “dishonest hooligans” but said NOAA can’t recognize that the project is now in responsible hands. He and several others who quit in the coup have since returned. “They’re different,” he said. “They’re taking a measured, considered approach to this.”

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.