When Ali Rahimi arrived in Austria in September 2015, he was full of hope. Hope that he would be able to live in peace and learn to read and write. Since his deportation, he lives in constant fear for his life.

Until the moment he made it to Austria at the age of 16, Ali’s short life had been filled with fear and struggle. He grew up afraid not only of the brutal Taliban in his hometown of Ghazni, south-west of Kabul, but also of violence at the hands of his own father, of beatings which had left him unable to concentrate and learn at school.

When Ali was just 11, his father dragged away him from his mother and siblings to Iran, where he was forced to work laying tiles. His father kept all his earnings. Living illegally in Iran, Ali — an ethnic Hazara — was a prisoner, “locked up like an animal.” When he turned 16, his father took their money and returned to Afghanistan. Ali was left alone in Iran. It was 2015. Then he saw a glimpse of hope. Europe was opening its borders.

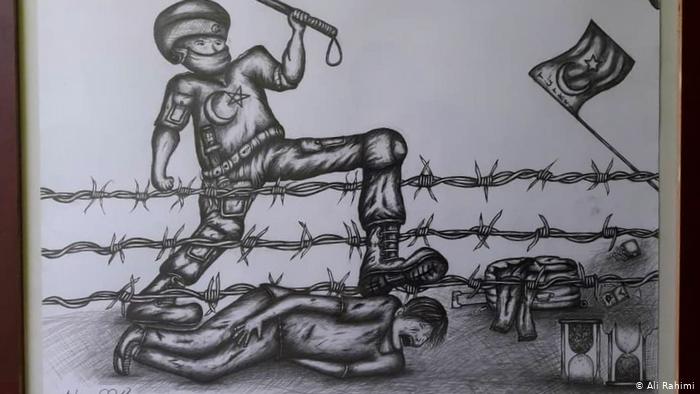

It took Ali a month to reach Austria. He applied for asylum at the Traiskirchen refugee reception center south of Vienna and immediately set about learning German. For the first time in his life, with “his head free from fear,” Ali “realized he was not stupid” and began to read and write. He made friends. From Traiskirchen he was moved to a home for youths in Graz, where he was given art materials. He taught himself to draw and paint by watching YouTube videos.

Two of his works were hung in the manager’s office.

A first setback

Ali’s first big blow came in 2016, when his asylum application was rejected. But he “stayed strong” and continued to study German and draw. He joined a football team, learned to swim, dance, ski and ice skate, and was “certain he would be allowed to stay in Austria.” He had an Austrian girlfriend, Anna, and they planned to marry. In March 2016, Ali held an exhibition of his artworks in Graz and by 2017 he had illustrated and published his first book: a children’s story called “Vaiana und Maui — a small story about a great love.”

“I had so many plans for my book, and for more books,” writes Ali in fluent German from Kabul. But in 2018, he received his second rejection. “My heart broke. I could no longer smile. I had no more chances. I had to leave Austria.”

On the advice of a lawyer, Ali went to Germany and applied again for asylum in Munich. But there he was told he had to return to Austria. “I cried and begged them to give me a chance to stay and be an artist. But they put me into Schubhaft (detention pending deportation).” After one month incarcerated in Germany, Ali was sent back to Austria. Again he was locked up, this time near Graz. Each week, representatives from the organization Menschenrechte Österreich (Human Rights Austria) visited him. And each week they told him to sign a document agreeing to his return to Afghanistan. “They said that if I didn’t, the police would deport me by force, and it would be better for me if I went voluntarily.”

One week after signing, Ali was sent back to Afghanistan: from Graz, to Vienna, to Istanbul, to Kabul. It was July 2018. A representative from the International Organization for Migration told him he would receive €2,800 ($3,175) to help him settle and start a business. He got €500. At first he was sent to a hotel in Kabul, so dismal he contemplated killing himself. Then he managed to contact his mother, for the first time since he was 11. He could hear the fear in her voice when he said he would come to Ghazni, which had recently been taken over by the Taliban.

Pariahs in their own country

There was no way to see his mother and siblings without his father knowing. Ali was terrified, and with good reason. His father was beyond furious to find his son back in Afghanistan.

Afghan society for the most part believes that “only criminals are sent back from Europe.” Those who return are seen as failures who have brought disgrace upon their families. “They think we are drinking alcohol, smoking, doing drugs,” writes Ali. And to the fundamentalist Taliban, returnees from the decadent West are “infidels” and “enemies of Islam,” who deserve nothing less than death.

For the first days Ali’s father refused to say a single word to him. When Ali called him “Papa,” his father beat him. “He said to me: ‘I am not your father, you asshole, get out of my life you animal.'”

One night Ali’s father tried to force him to take up a weapon against the Taliban, who, as Sunni Muslims despise the Shiite Hazara majority in Ghazni. Ali refused, and his father beat him again. When Ali fled to Kabul, his father beat his mother so badly she was hospitalized. And when Ali tried to return to bring his mother and siblings to safety, he was stopped outside Ghazni by a group of heavily armed Taliban. One Talib took his phone and discovered messages in German to Ali’s friends in Austria. Again Ali was beaten and whipped with a belt, and his phone smashed. When he finally got home to rescue his mother, his father discovered him, beat him again and locked him up with their animals.

No respite

By November 2018, Ali knew he would not survive if he stayed in Afghanistan. He made his way to Nimroz province, in the south, and paid a smuggler to take him back to Iran where he found work laying tiles, again illegally. He worked 12 hours days, living in hiding, in fear. But still he drew and dreamed of Europe. For five months he saved, and made it as far as Istanbul. There he was imprisoned with 2,000 other young Afghans. Every day they were beaten by Turkish guards and after three months Ali was sent back to Afghanistan. He was now 21, and exhausted.

Ali is one of around 20,000 Afghans who have been sent back — either “voluntarily” or forcibly — to Afghanistan from the EU since 2015. Refugee rights activist Doro Blancke of Fairness Asyl says hundreds more young Afghans like Ali in Austria are now living in fear of deportation. Many are in hiding, traumatized and depressed.

“Europe says Afghanistan is safe,” says Zaman Sultani from Amnesty International. “But ask if they would travel without an armored vehicle from their own embassy within Kabul, let alone in the provinces.” Sultani says deportees cannot return to their home villages because of extreme levels of insecurity and fighting between Taliban, “Islamic State” forces and corrupt local commanders. The danger has escalated even further since the signing of the US-Taliban peace treaty in February, after which more than 5,000 Taliban prisoners were released.

Since his second return to Kabul in mid-2019, Ali has been accepted into an art school established by Robaba Mohammadi, a teenage girl who paints and draws using her mouth. He’s learned to read and write in his native Dari, and has written his second book in German. But the anxiety never stops. In March, Robaba’s studio and school were hit by a bomb. Two of his colleagues were seriously injured. “If the Taliban find out I am an artist,” he writes, “they will cut off my head.”

DW / Balkantimes.press

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.