Racial profiling is banned in Germany, yet people of color say they’re arbitrarily stopped by police every day, describing it as public humiliation. There’s a heated debate whether a probe into police methods is needed.

Outrage has swelled in Germany over Interior Minister Horst Seehofer’s decision to block any plans for a study into racial profiling in the police force. He said that the practice is already banned, it is unlikely to be happening at a large scale.

The term “racial profiling” refers to the targeting of ethnic minorities by police officers, who conduct stop-and-search checks based on skin color.

Anti-racism campaigners, who have been talking about the issue for years, if not decades, were quick to insist that a study is long overdue.

An official government study would be “essential,” according to Tahir Della, spokesman for the Initiative of Black People in Germany (ISD). “We have as good as no data about complaints against the police,” he told DW.

Justice Minister Christine Lambrecht, a Social Democrat, contradicted Seehofer’s argument: “This is not about putting anyone under general suspicion,” she said in an interview with public broadcaster ARD. The point was to “establish the facts and to know where we stand and how we can counter it.”

Pressure from the unions

Rafael Behr, a former police officer and now a professor at the Hamburg Police Academy, suspects that police trade unions, often outspoken about protecting police officers, pressured Seehofer into making his declaration.

“For a minister to say right out he doesn’t want this study — that did surprise me quite a lot,” Behr told DW. “It’s an opportunity that was missed.”

Racial profiling has been officially banned in Germany since at least 2012, when a court in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate concluded that racial profiling is illegal because it violates the anti-discrimination article of Germany’s constitution, known as the Basic Law.

The incident that led to that verdict occurred on a train when a federal police officer demanded to see the identification papers of an architecture student living in Kassel — specifically because he had dark skin, as the officer freely admitted in his testimony.

Public humiliation

Since then, the police are supposed to make decisions on who to stop based solely on “objective” factors, such as suspicious behavior.

For several years, the discussion about police racial profiling was fueled by the emergence of an internal term used by police in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia: NAFRI, an acronym meant to designate “Nordafrikanische Intensivtäter” — “North African repeat offenders” — but in practice applied to identifying and surveilling North Africans in general.

In 2013, the German Institute for Human Rights (DIMR) conducted its own survey and concluded that state and federal governments urgently needed to address the of racial profiling, because the practice reinforced racial stereotypes both in the police and the population at large, damaged the integration of minorities in society, and eroded trust in the police.

The term became famous when it was used in police communication to describe the incidents at Cologne central railway station on New Year’s Eve of 2015 when groups of young men, many of which were of North African and Arab origin, carried out sexual assaults during the celebrations.

Left and Green party politicians were quick to denounce the term, as did the federal Justice Ministry.

In 2018 a court in Munich ruled that authorities could use skin color as criteria for their work in cases “when the police have concrete indications that persons with darker skin incur criminal penalties over-proportionally more often” in a certain area.

Biplab Basu, the founder of the campaign for victims of racist police violence (KOP), explained that racial profiling is not about just about being hassled by a uniformed officer. “It’s basically the opposite of what is supposed to happen,” he told DW. “First the police look for a criminal and then they look for a crime.”

“It humiliates people in public, and it leaves people feeling completely powerless and at the mercy of anyone in uniform, and it means that white people around them see them as criminals,” he said. “It has a very, very strong psychological effect that stays with people for decades.”

Racial profiling can be deadly

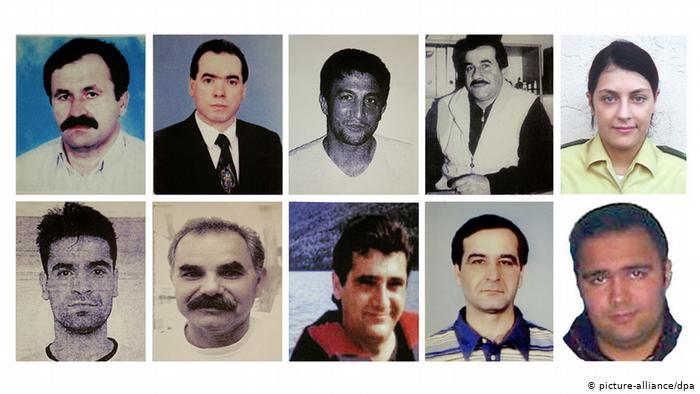

Tahir Della also pointed out that racial profiling can have deadly consequences, pointing to the premeditated murders of immigrants by the right-wing extremist National Socialist Underground NSU.

According to Della, these murders by a neo-Nazi terrorist cell happened partly because the police pursued immigrants of color as murder suspects, rather than the far-right. “Because of the powers the police have, racist thinking and norms can lead to people dying,” he said.

The idea for a new study was suggested by the latest report on Germany by the European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), funded by the Council of Europe, which roundly criticized institutional racism in Germany.

The problem, though, is what a study into racial profiling might look like: “No one knows,” said Behr. “If I was asked to produce a study like that, I’d have to think for a long time about how you would get at such data. You can’t just do a voluntary online survey [among officers] and say: Have you experienced racism? You’d have to think about a good way to produce objective data from a large, representative sample.”

DW / Balkantimes.press

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.