We were waiting for Ozzi at a cafe restaurant with a wonderful holiday setting, located on the corner of the Carpet Museum. In front of the Topkapi Palace stood a magnificent oriental style building with a flat roof with domes with gilded tops. Before entering the gate, Ozy stopped and explained to us that this stylized building was where the broth and sherbet were distributed to poor citizens, and there was the Sultan Ahmet’s fountain.

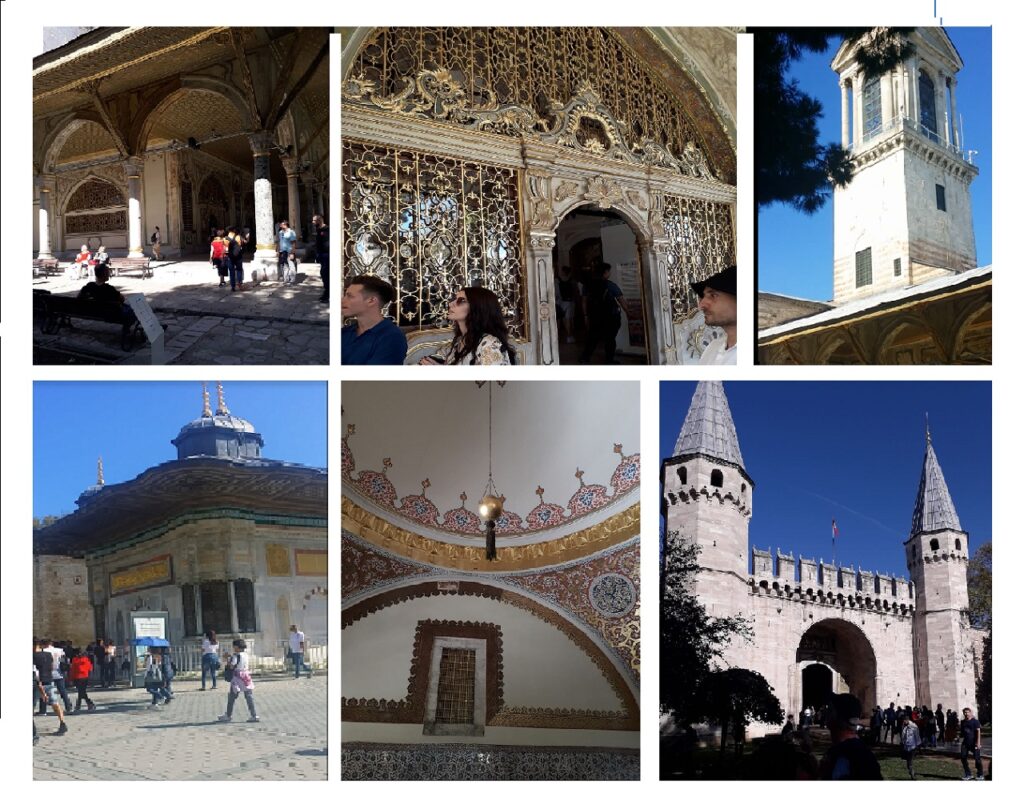

We were in front of the first door of the Topkapi Palace, on whose pillars and walls, even the bark of the trees, the most intimate, mysterious chronicle of the empire was recorded. Topkapi was the place since the 25 Sultans ruled until in the 19th century the Sultan’s court moved from the Topkapi Palace complex to the Dolmabahce Palace. Topkapi is where the empire peaked, but that’s where its downfall began.

A few years after the occupation of Constantinople by the Turks, construction began on the first Ottoman palace in the old Byzantine Acropolis, built still under Emperor Septimius Severus. Topkapi Palace (“The Palace at the Cannon Gate”) was protected by ancient Byzantine walls about two kilometers from the sea side, and a thousand four hundred meters built by the Turks separated it from the city.

Topkapı Palace is located on a hill above the old city of Istanbul, surrounded on three sides by the Marble Sea, the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn, spanning four yards and 700,000 square feet of gardens, buildings, gates and fountains. It is a whole small town, full of buildings of different styles and for different purposes, buildings with a large number of inhabitants who lived under military protection. There were public executions of those who disobeyed the Sultan’s orders, and almost all political conspiracies and riots took place.

Topkapi is a place with treasures full of gold and precious stones, ruled on three continents east and west. For 400 years, Topkapi Palace was the center of the Ottoman Empire, visited today by about 2 million tourists, its real name is “Sarayi Jedid and Amira”, but because of the large cannons at the gate’s entrance, the people called it Topkapi.

The architecture of the palace was reminiscent of the organization of a tent during a military hike, which is not surprising given that Mehmed II intended to use Topkapı as a winter yard at the time of the hike. The topkapi is divided into two large parts: birun and enderun, into four yards. In birun, the outer part has the first and second garden, while the enderun or the inner part belonged to the third and fourth garden.

We arrived at the palace walking past Aya Sofia towards the imperial door, through which we entered the first courtyard. The garden in the courtyard was full of greenery, some of the buildings were on the edges, the interior was filled with trees, I expected to see at least some barn, but it did not happen.

The first courtyard of the palace

The first door was open to all, where citizens could submit their requests to officers employed in the offices in the yard. The first thing I noticed to the left of the gate was the fourth-century church of Ai Irene, which is considered to be the oldest church in the city. It was built by Emperor Constantine in the fourth century, and the Ottomans turned it into a weapons store.

In the Ottoman period there was a library in this courtyard, in which books were bound in leather. To the left of the courtyard was the imperial blacksmith shop, where gold and silver coins were struck. The first garden was also used to house officials who connected the Sultan and the outside world: as an artist, or to house buildings such as a forge or a janitor’s armory in the church.

Dželat-česma

After a brief hour of our guide’s history, we hurriedly made our way to a castle-like door called the Greeting Gate. Only the Sultan was allowed to enter through that door, and the rest had to walk through that door. All but government officials were required to obtain a special permit to enter this door. I’m thinking what would the Sultans think about the visitor river to this complex? It used to be a VIP, a place only for the privileged, and now the ‘ordinary’ people from all over the world went there, just enough to buy a ticket, which allowed them to peer into the most intimate corners of the once great empire.

Second door of the palace – The door of salutation

We entered the second courtyard of the palace through the door of Greetings, decorated with an arched vault and two European-style towers. Above the arch stood black panels with gilded inscriptions in Arabic. The door led to the center of the complex. The second courtyard was used for the administrative purposes of the empire, there were buildings: such as sofas, treasuries as well as buildings intended to serve the palace’s inhabitants, such as kitchens or barns. These yards also have a hsitorial role. In this part of Topkapı, decisions were made about the future of the empire (divan councils). Decisions were made in places accessible to the public in another courtyard. Then, when the decisions were made by counciling on a wonderful empire, it was stronger. As they began to be brought inside the private rooms of the Sultan, and later in the harem, the empire weakened.

Divan, the entrance to the Divan, the conference room with the golden grille behind which sat the Sultan.

The most prominent site of this courtyard is the Tower of Justice, or Imperial Divan, erected above the Council of Ministers, where senior military and civilian officials were convened to make decisions about the empire. Interestingly, the Grand Vizier presided over these meetings, not the Sultan who listened to the meetings behind the gold cloth in the back of the chamber. If the Sultan disagreed with the decision, he would close the curtain. The video above shows a room where the leaders of the empire were counciled and a golden grid behind which the Sultan listened to the debate.

Topkapi housed the best in all spheres of public life: the best poets of the empire were court poets, the best architects were court architects. By designing court art as well as behavior patterns in Topkapı, the culture of the entire empire was shaped. The Harem-educated women who would have been married would transfer their model of behavior and their education to a new environment. The students at Enderun School were the best officials, they transmitted their education throughout the empire. In the second courtyard next to the imperial sofa is the treasury building, in which the scribes recorded the treasure and expenses of the empire. Today, the Treasury houses a museum of weapons and armor of the Ottoman Empire.

Treasury, interior divan, list of ministers, vizier at the entrance to the divan

Another important place in the courtyard was the Imperial Kitchen, which extended all the way to the right of the courtyard.

Kitchen

Opposite the Imperial Divan is a kitchen, where meals for about 5,000 Palace staff are prepared daily. At religious holidays or imperial celebrations, that number would reach 15,000. The kitchens at the palace also produced soap and herbal remedies for the Sultan and his family.

For the first time the kitchen was built during Mehmed II and later in the 16th century during the reign of Selim II the kitchen was restored by Mimar Sinan. About 1200 people worked in the kitchen at the time. The kitchen has three parts: one for the sultan, one for the rest of the staff, and one for the sweets – helvehans. The Imperial kitchen with large chimneys occupied the entire right side of the courtyard. The kitchen had many rooms and was used to store food for the whole complex. The kitchen, which consisted of two parts, employed 60 cooks and 200 assistants. 20,000 meals were prepared daily, which means that besides three daily meals for 5,000 inhabitants of the palace, 5,000 meals were also prepared for the sake of national cuisine.

Each chef was a specialist in preparing certain types of dishes. At the end of the kitchen was a section for making sweets and helvehana treats. A deputy Sultan’s confectioner invented a rahatlokum in that kitchen. Various treats were prepared, kmpots, baklava. A special part was occupied by the Sultan’s kitchen, in which about 30 cooks and assistants prepared meals for the Sultan alone;

While the kitchen was preparing a variety of food, bread was baked in a bakery located in the yard. Today, there are 186 formulas for making medicines dating back to the Ottoman era. Much of the kitchen complex is home to the third-largest porcelain collection in the world today, but there are only a small fraction in the showrooms. One part of this porcelain was acquired in the conquests, one part is the gift of ambassadors and other high officials, and one part is the treasure of deceased rulers. According to some accounts, it is believed that in the case of poisoning in food, porcelain made in the time of Celodon changed color, so the sultans ate from these dishes.

At the end of the hall next to Helvahana are exhibited glass items made in a glass workshop in Istanbul intended for palace purposes only, as well as glassware from Venice. On the other side of the hall are silver objects handcrafted by a master in the palace and items brought to the palace from countries around the world.

At least 65,000 exhibits were displayed in Topkapi, which is only one tenth of the total collection of the palace. This is a truly incredible monument, it literally shows the breath of the time. It was difficult to circulate all these buildings with about 55 tons of gold. There are about twelve thousand pieces of porcelain there, including white porcelain exhibits that are unlike anything in Europe. Most valuable exhibits and historical archives are kept in treasuries that are not accessible to visitors and are kept by the police.

At the end of the second courtyard was the ‘Gate of Fortune’, the door leading to the third courtyard and the interior of Topkapi Palace. What lies behind that door will be read below.