Alexei Navalny, a fierce opponent of Russian President Vladimir Putin and the country’s most prominent opposition figure, is lying in a coma in a Siberian hospital after an apparent poisoning.

As the world reacts in shock to what looks like an attempt on Navalny’s life, there’s a side to his career that risks being overlooked. Though he’s best known outside the country as an opposition politician, his most enduring legacy may be as the producer of an unorthodox, but highly effective, brand of investigative journalism.

No one would claim that Navalny is in any way impartial. He’s the one, after all, who coined the epithet “party of crooks and thieves” to describe Putin’s United Russia. And he’s had a long career in Russian politics: He has worked with the liberal opposition party Yabloko, co-founded the now-defunct right-wing Narod movement, run a spirited but ultimately unsuccessful campaign for mayor of Moscow, and attempted to challenge Putin for the presidency in 2018.

The Bristol property secretly owned by the controversial governor of the Bank of Lebanon

But his presidential ambitions ended with a politicized disqualification, and it has become clear that Putin’s carefully managed system, which uses the trappings of democracy as a fig leaf for muscular authoritarianism, will never allow him to break through using retail politics.

In these circumstances, Navalny has made anti-corruption activism a key — and wildly successful — plank of his political work.

In so doing, he has become one of the country’s best investigators, using painstakingly documented proofs and slickly produced videos to expose the corruption at the heart of the Putin regime. Whether or not Navalny ever holds public office, it is this exposure of modern Russia’s rotten underpinnings that may end up being his most enduring contribution to the country.

His video investigations are exemplars of the genre, deftly employing drone footage, high-quality animations, and wry humor to make complex schemes clear and understandable to ordinary people.

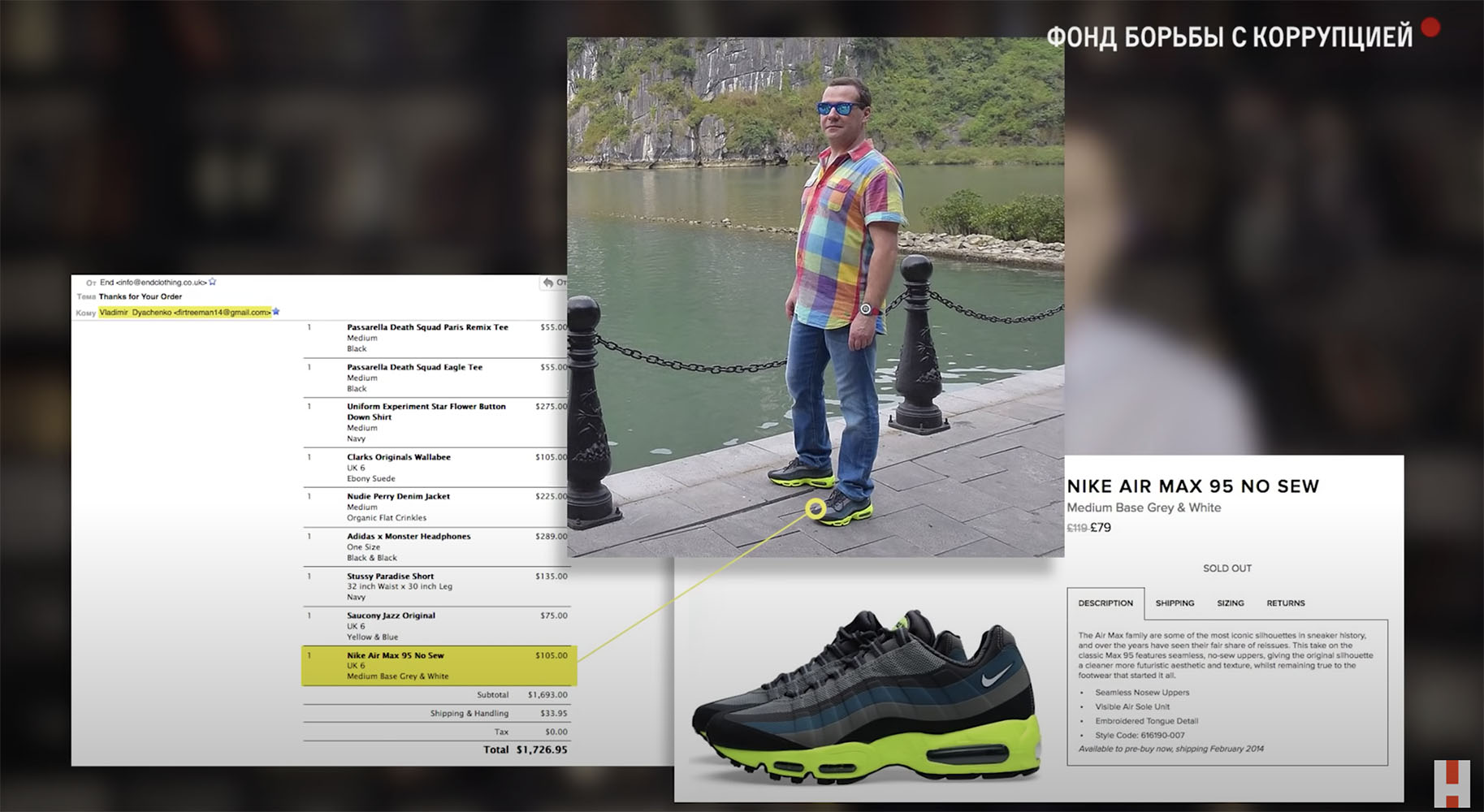

Navalny’s best productions also manage to turn the investigative process itself into a compelling story. In perhaps the best-known example, his investigation into former Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s wealth begins by explaining how a purchase receipt for a pair of expensive Nike sneakers, matched to a publicly released photo, led his researchers to an address that ended up revealing a real-estate empire.

It’s no surprise that Navalny’s top five investigative stories alone have racked up over 82 million views on YouTube.

For specialists and those looking to delve deeper, the films are accompanied by lengthy, multi-part texts that painstakingly explain the underlying documentation. Beyond simply stating the facts, the texts are wrapped in explanatory language that highlights how unearned wealth underpins the corrupt system Putin has built.

Navalny’s biggest investigations:

Don’t Call Him Dimon

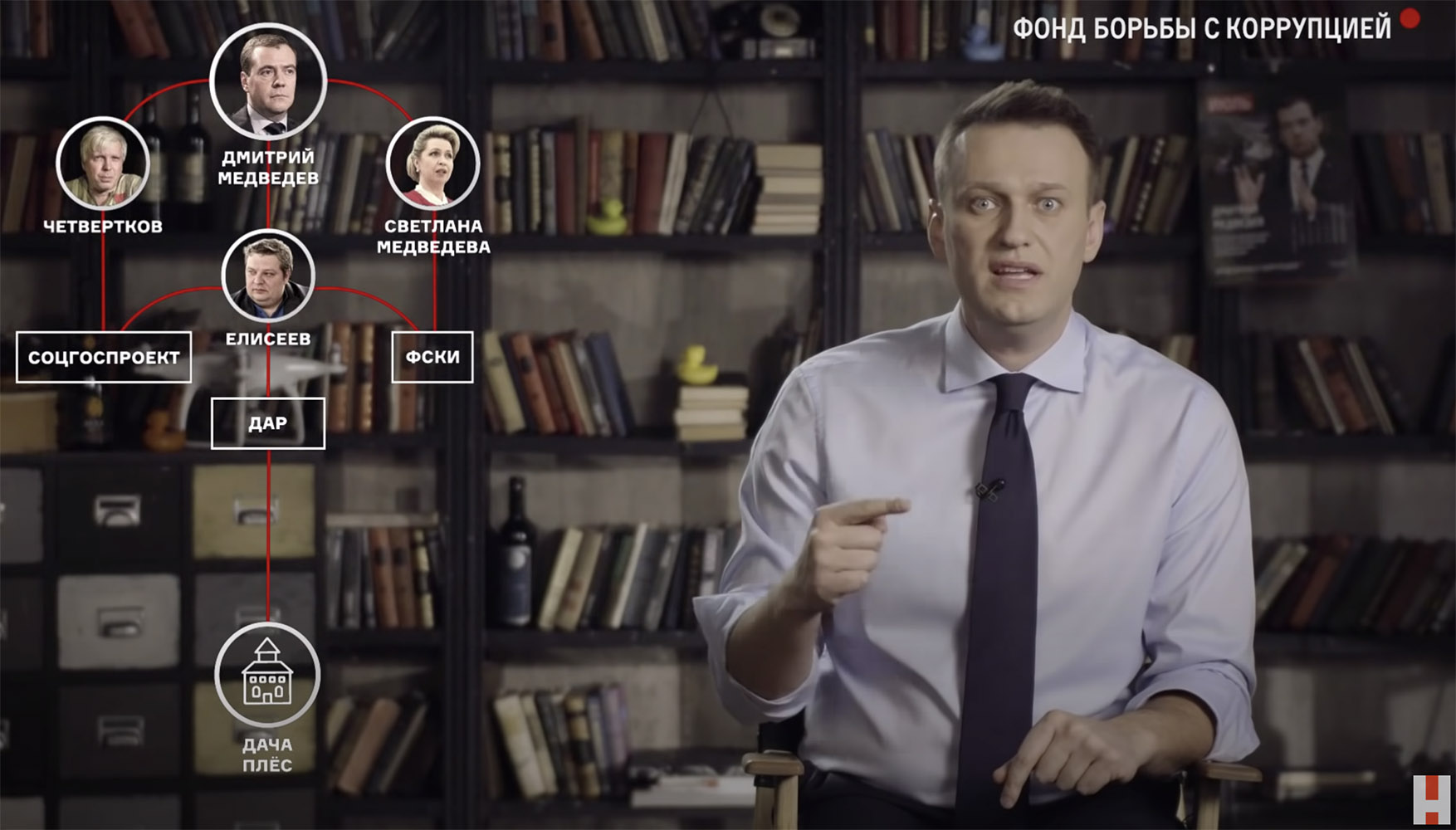

In a flagship investigation that has racked up over 35 million views, Navalny showed Russians that their then-prime minister, Dmitri Medvedev — known as a relatively friendly face with a love of high-tech gadgets — is in fact one of the country’s wealthiest people. Through a network of charitable foundations controlled by close associates, Medevev holds vast plots of land, mountain resorts, apartments in pre-revolutionary mansions, yachts, and other luxuries. (View on YouTube)

Chaika

In a 2015 investigation, Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation focused on the family of Russia’s then-prosecutor general, Yury Chaika. The film and accompanying text accuse Chaika’s two sons of using their father’s connections to illegally enrich themselves, describing a series of corrupt schemes that involve ties to a murderous gang, illegal privatizations, and shady state construction tenders. The profits of these schemes, the films explained, were plowed into foreign investments, including an ultra-luxurious Greek hotel and a Swiss villa. (View on YouTube)

From an English Prison Into the Russian Elite

In this 2017 investigation, Navalny’s team exposed the glamorous lifestyle enjoyed by Nikolai Choles, the son of Putin spokesman Dmitry Peskov. Choles, who has been only sporadically employed and has served time in prison, reportedly enjoyed a life filled with expensive cars and properties, yachts, private jets, and horse jumping competitions. His success, Navalny said, is “an example of how, in Russia, where 20 million people live beneath the poverty line and 70 percent can only dream of a salary of 45,000 rubles, it is possible to have a wonderful life. At the highest level. Without doing ANYTHING.” (View on YouTube)

Putin’s Secret Dacha

Navalny begins this 2017 video with a cry of frustration: “I’m mad and upset and sad. I’m pulling my hair out.” The reason? His team had been scooped, with the independent Dozhd TV channel beating him to the revelation of an opulent dacha owned by President Putin outside the city of Vyborg. The remainder of the video shows “what Dozhd didn’t have,” giving viewers a guided tour of the property filmed by drone, and explaining its ownership structure. (View on YouTube)

Roman Anin, a member of the OCCRP network and the editor of one of Russia’s newest investigative outlets, IStories, makes no bones about Navalny’s impact.

“Of course,” he acknowledges, Navalny’s investigators “don’t follow journalistic standards and never try to listen to the other side, which saves them time and makes their stories simpler to understand. But I still believe we [journalists] in Russia lose to them in terms of effectiveness.”

“He has created probably the most effective investigative media outlet in the country,” Anin says. “The number of stories they publish, the creative way they find the stories and deliver them to their audience, is something we should learn from.”

In a screenshot from an investigation into then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, Navalny explains the ownership structure of an opulent countryside dacha.

Navalny’s own staffers make no pretense of being impartial. In an interview with the outlet Meduza, his spokeswoman Kira Yarmysh was clear: “We aren’t journalists,” she said. “If we don’t like something and we consider such-and-such person a crook, then we can call him a crook directly.”

Nikita Kulachenkov, one of Navalny’s investigators, made the same point. What his team does is “something between journalism and politics,” he says.

But the work he describes at Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation sounds very much like a small investigative newsroom.

He and two other principal researchers work with Navalny to identify topics that are both newsworthy and lend themselves to the group’s preferred format of video presentation.

“Sometimes we have to investigate particular areas or people because of political developments,” Kulachenkov says. “Now there are elections in several regions, so we’re focusing on that. Last year there was an election in Moscow, so we focused on Moscow, researching United Russia candidates.”

The team thinks carefully how to maximize the appeal of their stories, particularly since it depends on viewers’ donations to stay financially afloat.

“We didn’t start with YouTube from the beginning,” Kulachenkov says. “But in 2015 we released the [Prosecutor General Yury] Chaika movie — that was our first investigative movie. It was hugely successful by YouTube’s standards at the time … and we thought: ‘we have to switch to YouTube, [as it] spreads more than any articles.’”

And like any professional investigative journalists, the Anti-Corruption Foundation is also concerned about credibility. “We always publish the documents that are the base for our conclusions,” Kulachenkov explains. “We understand that some people would like to check and proofread them .… We have backing for every claim we make.”

The usual official response to the corruption Navalny uncovers is usually total silence, Kulachenkov says. He describes this as a symptom of living in an undemocratic country where public servants feel no accountability to an electorate. But the team has also faced repeated lawsuits. He says that more underhanded tactics have also been employed. One colleague who, unlike him, has remained in the country, is sometimes followed by unknown men.

And he suspects the Anti-Corruption Foundation’s office has been bugged: “[We] discuss something on a call, and a week later we see that the Cyprus companies start changing their shareholder structures … I don’t think many journalists have this kind of privilege,” he jokes.

Navalny’s work is no substitute for real, independent investigative journalism, of which Russia has far too little. But in repeatedly revealing the ugly face of the Putin regime to his fellow citizens, he has done what few journalists could.

“I know several of his investigations almost by heart,” says Olesya Shmagun, an OCCRP reporter. “For a long time he was able to maintain the perfect balance of humor, well-founded criticism of officials, and an incredible optimism: That not everyone is like this. That we can be different.”

And even among the general public, he has inspired a fervor that few other Putin opponents can match.

Nina Jankowicz, an author and Eastern Europe specialist, recalls a striking example from her stint as an election observer in a small, snowbound village outside the city of Togliatti in southwestern Russia.

Navalny had been disqualified from the 2018 presidential election, leaving only Putin, TV personality Ksenia Sobchak, and several minor candidates on offer.

But at least one voter had had enough. In the small plastic voting booth, scrawled multiple times across the flat surface used for marking ballots, was Navalny’s name.

Napomena o autorskim pravima: Dozvoljeno preuzimanje sadržaja isključivo uz navođenje linka prema stranici našeg portala sa koje je sadržaj preuzet. Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku The Balkantimes Press.

Copyright Notice: It is allowed to download the content only by providing a link to the page of our portal from which the content was downloaded. The views expressed in this text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Balkantimes Press.